About this week’s show:

- Memories of an un-ended War: David and Don McAlvany’s visit to the Korean DMZ (see pictures)

- Silver up 12%, Gold up 11%, Nasdaq up 8% YTD: Need we say more?

- A list of potential Triggers that will take gold to a 1/1 ratio with the Dow

The McAlvany Weekly Commentary

with David McAlvany and Kevin Orrick

“On today’s show we will talk about Dave’s visit to the demilitarized zone, the DMZ, in Korea, and what to do to take advantage when everyone in the world is buying gold except people in the United States.”

– Kevin Orrick

“I think you have a reasonable number of possible – let’s call them risk, or force, multipliers – and I can’t tell you which geography will move to front and center, which will be in the limelight, which will be the mother of all concerns. But here is what we do have today. Here is what we know we have in the pipeline. The mother of all debt problems is already here, and the mother of all geopolitical conflicts, very interestingly, may not be far behind it.”

– David McAlvany

Kevin: Dave, you fly more than probably anybody that I know, and I know there is always this concern that you can plan a three-leg or a four-leg trip, whether you are going to Dubai, or whether you are going to Beijing, what have you. And literally, it is still random as to whether you are going to get bumped from a flight.

David: You know, what is interesting is, I haven’t flown as much this last year, and so I lost my platinum status with United, and I have never felt more vulnerable in my life.

Kevin: Do you think they might pull you off the plane at some point?

David: (laughs) Who knows? My favorite laugh of the week, last week, was the Pentagon awarding the contract to United Airlines to forcibly remove Assad.

Kevin: Oh boo, boo. Okay, so United. Yes, they could probably do it better than 59 Tomahawk Missiles. I wonder if they should do the same thing with North Korea?

David: Hey, you know what? Maybe the contract is out. In the region, speaking of North Korea, you have a few of our destroyers, and now one U.S. aircraft carrier, with rumors of more being sent. And it is clearly a staging area for something, if need be. A show of force? Perhaps. A muscular form of saber-rattling? Definitely. And can it materialize into something more? We will get into that.

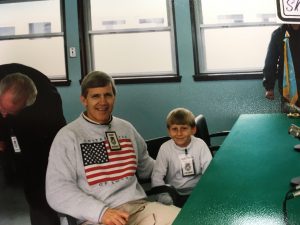

Kevin: Dave, I remember 1992 when you had gone with your father and your brother to South Korea. But you had special VIP privileges. I think you went into the negotiating room, right on the DMZ. You got a chance to see some tunnels. I know Don, when he came back, explained that you could view the guards. They stood behind these giant concrete pillars with only one eye exposed, continually looking at the other side of the border. Tell me a little bit about that.

David: It reminds me of the way Jim Rogers opens his book, Street Smarts. He says, “For me, understanding history and its consequences has not been an armchair endeavor, but a hands-on adventure.” Traveling with my dad – that is certainly a part of the family legacy that he created. Our understanding of history is very much alive. It is not from texts, it is from places that we have been, things that we have touched and tasted and smelled and seen. In this case, we were in South Korea. I think the last time I was there is when I was 15 when we went on a VIP tour of the DMZ. We went to the border, Panmunjom. We viewed the guard house, from which a showdown with the North Koreans had occurred over a tree that was obstructing a view of the road.

Kevin: Yes, didn’t somebody want to cut it down and that almost led to an incursion right there?

David: That’s right. Cutting down the tree nearly triggered a war. Just as a reminder, the triggers that create major conflict aren’t always predictable. You can go back to World War I – here we are celebrating close to 100 years since that timeframe. And what was it? It was a terrorist attack. It was a singular event. And you end up with the British and the Germans royals who were on friendly terms and vacationing six months earlier, now sending their boys and girls in to die in the trenches in France and throughout Europe.

Kevin: If you think about it, those guys who were in the trenches all the way up to the end of that war really couldn’t explain why they were there. The alliances had been so complex that when they broke down they were shooting at each other but couldn’t really explain the dynamics of why.

David: I will go ahead and post the pictures on the show so you can see them.

Kevin: You were taking the picture.

David: And come to think of it, I was not allowed to go onto the North Korean side. Neither was my dad. We sat on the UN buffered side. And then there was the North Korean side, and I think I might have stretched over a little bit just to take the picture.

Kevin: (laughs) Always the rebel.

David: The reality was, even then, there was protocol to be followed. We may have been on the border, but you shall not pass. Do not break the clothes, in actual legal terminology. Again, history comes alive. After that we explored the fourth invasion tunnel, if I recall correctly. It could have been the second.

Kevin: Those were tunnels that were secretly dug so that the North Koreans could invade South Korea if they wanted to, right?

David: That’s right. The fourth was dug under the DMZ, the Demilitarized Zone, and was discovered in 1990, just a short time before we went into it.

Kevin: And they were huge, weren’t they?

David: Yes, some of them were very large. This one was blockaded, barbed-wired, mined, and set up with a large machine gun. So you would go down into the tunnel and they have it sort of plugged up partway down. But you’re right, other tunnels like it were dug to allow for the passage of as many as 30,000 troops per hour through the tunnel, and were large enough for both military jeeps and small tanks to drive through to facilitate a full-scale invasion.

Kevin: I think we should remind the listeners, this was an agreement that was reached but the war never really ended. That war still goes on, in concept.

David: I don’t have my dates exactly correct, but you’re dealing with a peninsula that had been thrown into chaos, invaded and taken over multiple times, 14th century, I’ll just say something like 1392, and then in the 16th century again when the Japanese invaded. And then in 1910 the Japanese invaded again, and held it through the end of World War II, at which time it was divided up. So from 1945 forward, the country was divided north/south, Communist North, more democratically oriented south, Western-leaning South Korea. And it wasn’t until 1950 that North Korea did invade.

Actually, what is interesting is that most of the tunnels, one, two and three, I think, date to discovery in the 1970s, so from the 1950s forward they were still planning a full-scale invasion. Then they found a brand new tunnel in 1990. Maybe, like the tunnels that are dug under the Egyptian/Palestinian borders, and in Mexico, too. It is just a question of, constantly it is occurring, and how many have been discovered, or are currently in progress?

Kevin: And not just tunnels, they’re still making missiles. Let’s face it. You either do it through a tunnel under the ground, or you do it with a missile over the ground, but there is still tension, when you’re there, isn’t there?

David: Yes. I remember being a young teenager and appreciating the constant threat from North Korea. When you drive the highways of South Korea you can see signs of preparation all around you. The highway overpasses, for instance, are all overbuilt, and what that allows them to do is, in a moment of crisis, come along and blow those bridge overpasses and block the motorway beneath so that, again, tank and troop transport is very difficult through the vital arteries of the country. So, it’s a country that has maintained a war footing for a long, long time, since the 1950s invasion, which I mentioned, following that formal separation in 1945 at the close of World War II.

Kevin: Dave, you talked earlier to us about game theory, and rational actors versus irrational actors. Now, if you’re going to play a game with somebody you are assuming a rational actor. In other words, the rational actor would want to win, but not necessarily at the cost of total destruction of themselves. And you’ve talked about World War I, which actually started with an irrational act. It was an execution of leaders in Sarajevo. It was an irrational act that actually started a huge chain reaction of wars against what we would call rational actors.

David: Yes, it is interesting, one of my favorite books on the topic, Arms and Influence, by Thomas Schelling, looks at some of the issues involved in game theory. He kind of brought game theory to international relations. I would love to have him on the program. He is still a professor emeritus at Harvard. I have invited him several times and he says, “I’m on vacation, I’m on vacation.” So, one of these days, the conversation with Thomas Schelling will occur.

Kevin: We can’t talk to Von Neumann who actually put the math together back in the 1940s because he has passed away, but it’s math.

David: But here is the problem with the math. The Rand Corporation puts together the mutually assured destruction, the idea that drove the cold war competition, the arms race, where we are pitting ourselves against the Russians to build and have just one more bomb than they have. And of course, what that theory assumed was that if we have the equivalent amount, no one will do anything because it’s mutually assured destruction. Everyone loses.

Kevin: They’re rational actors. Right.

David: But the problem is, and if you look in the side notes in my copy of Arms and Influence, you will find questions all about how you deal with non-state actors, who may have a different set of motivations. What I originally thought in terms of was somebody like ISIS, ISIL, Al-Qaeda, the Mujahidin. You’re talking about groups of people through recent history who don’t necessarily have a calculated direction. And I think you have that same issue with North Korea. Game theory assumes rational actors. Introduce a non-rational actor into the mix and how does game theory work. And quite frankly, anything can happen.

Kevin: You know what it reminds me of, Dave? Did you see that Batman movie with Heath Ledger playing the Joker? Now, he understood game theory. In the movie, it was brilliant, he set up several game theory scenarios for rational actors, yet he was irrational in his actions. And so he became a danger to everyone because they had no idea what he would do next.

David: Right. Well, I can imagine the North Koreans reacting, or over-reacting, to something the U.S. does, something more that maybe we have one too many carriers sitting in the water.

Kevin: Didn’t we send another one over there, as well?

David: It has been rumored. What if they connect us back to sabotaging the most recent missile launch, their show of force and bragging rights, that “We are great, we are powerful,” sort of projected propaganda, not only to the North Koreans but the rest of the world, “Don’t mess with us.” If we were actually involved, through hacking, having that thing blow up on the launch pad, what we are dealing with is an entity, a person, who is even more volatile, they have been shamed, and really, anything can happen next.

Kevin: Last week you talked about who benefits, and who maybe loses in the Syrian battle, but I have been sensing that China might have a benefit here because there is a distraction from some of their domestic problems. If we get over there, and we are on what they consider their turf, do you think maybe this has to do with China, a little bit like the dinner with the Chinese leader last week when Syria was struck?

David: Sure. You have the Mar-a-Lago meeting where Xi Xinping is there and responds to Trump, who says, “You have to solve the North Korean problem. This is in your back yard. And if you don’t, I will.” It would be interesting to see what the Chinese do with this because if we took out the nuclear capability of the North Koreans, China benefits immensely from having a regional skirmish, without the implications of nuclear war, of course, the regional skirmish, a conflict which is consistent with what they may need for engineered economic activity and production. War sometimes gives politicians the ability to fabricate production and productivity in the economy. Ultimately, I don’t think that is healthy, but nevertheless, it gives them statistical fodder.

Kevin: You could almost have the same thing with Trump, couldn’t you? Some of the distractions that Trump is seeing right now in the media, if we go to war or something, even if it is a regional war, people will start looking at that instead of whether we get a budget passed.

David: And I think it is particularly cute in China because you need to distract the population from domestic, political and economic concerns, have those things take a back burner. And as you say, Trump’s policy objectives – domestic, economic in nature – they become irrelevant to the degree that people fixate on conflict and war.

Kevin: It is called redirection.

David: That’s right. War is good for that – redirection of attention, redirection of pressure. And I would like to know the full extent of Donald’s conversation with President Xi.

Kevin: You called him Donald. Who is Donald? Who is the real Donald Trump? This is a guy who told me that he didn’t like the Federal Reserve, and he hated low rates, and he thought that the dollar needed to rise, and now he thinks the dollar needs to fall.

David: Before he took office, do you remember our conversation on that? We said, “Yes, he doesn’t like the Fed today, but when it is his economic bubble, and it is his stock market bubble, he is going to love the Fed, and he is going to love low rates.” So, what does he think? What does he believe? You are right, prior to the election he was critical of low rates, he was critical of monetary policy managed by Janet Yellen. Now it is his economy, now it is his stock market bubble. Lo and behold, any surprises here? No. Of course, he likes Yellen, he likes low rates (laughs). He wanted us out of NATO because it was a waste, because NATO was obsolete.

Kevin: Not any more.

David: But from the perspective there in the oval office, it is no longer obsolete.

Kevin: Remember China? He thought that they were the biggest currency manipulators in the world.

David: If he said it once, he said it a dozen times on the campaign trail. And they were going to officially be sanctioned as such, as currency manipulators. They are no longer a manipulator, and it is fascinating to watch President Trump, in a single breath, not only excuse the Chinese of currency manipulation, but practically finish that sentence with, “By the way, the dollar is too high,” and sends our currency to lower levels at the mere suggestion.

Kevin: A conservative that we have had on this program, David Stockman, who worked with Reagan, has come out and said, “Something really interesting happens on the 100th day of Donald Trump’s presidency.

David: I sat at a luncheon table with Jim Grant, Bill Fleckenstein, Mitch Cantor and David Stockman in New York two years ago. It is interesting to see the difference in personalities. Some people are slightly more pensive and quiet and you can tell that they are not verbal processors and just more internal processors.

Kevin: But not Stockman.

David: David Stockman is not only a man with fire in his belly, but boy is he a verbal processor. I don’t think he has to edit his articles when he writes them. I think they just flow perfectly, because actually, when he speaks, it’s powerful. It’s good. But there is this sense of irony from Stockman, that here we are coming up on the 100th day on Donald’s reign, and it is also the day that government cash runs out and the government begins going into shutdown mode.

Kevin: Yes, and he thinks that this could be a real showdown.

David: Right.

Kevin: Let’s switch over to stocks and gold for a moment. We’re in April right now, and every year, Dave – year after year after year – when it is April you say, “Okay, we’re coming into May and the old saying is, ‘Sell in May.’” And how does that finish?

David: “And go away.” If you were just looking at 100 years’ worth of information from the stock market almanac, what you would find is that there is a powerful seasonality, and that there are up months and down months. And if you literally took a portfolio and stepped away and did nothing between May and November, and were only invested for the last 100 years between the months of November and April, your performance is considerably better, because that season from the end of April, starting in May, through the end of October, where most of your declines occur. Basically, you are saying, I have most of the upside and I avoid most of the downside, just paying attention to that one seasonal rule, so here is the upward and positive seasonal bias in stocks. Guess where it typically ends? Yes, we’re coming up on it – April 30th.

Kevin: So, how does that affect gold then?

David: Thinking about gold, no move higher in the stock market, or certainly, a move lower in stocks, shines a very bright light – a spotlight – on gold here in the U.S. Asia has been buying, really, long before the North Korean tensions were on the rise, and they are maybe increase-buying in that region, depending on the results and if it moves toward an outright conflict.

As we discussed a few weeks ago, we have seen Chinese delivery off the Shanghai Exchange which has been very strong here in the early part of the year. And what that indicates is a strong demand for physical metals in China.

Kevin: I think you should differentiate, Dave, because you were there for the grand opening of the Shanghai Exchange. You were an invited guest. The difference between the Shanghai Exchange and the futures market here, which really controls the price on paper of gold. Explain the difference a little bit.

David: It does have more of an emphasis on physical metals, themselves. Clearly, they still trade in paper contracts, but they have a series of contracts which actually settle in kilo gold bars.

Kevin: That is why Shari’a law is allowing Shanghai Exchange contracts, and not New York futures contracts.

David: Because it ties to the real thing as opposed to just the paper game. It is one of the distinctive qualities of Asian, and specifically, Chinese market buying. That physical component is there versus the Western proclivity to play with paper or futures contracts. We trade for fun and profits. That is kind of how we play in the metals market, and they seem to be building a significant position – have been for years.

Kevin: They are not satisfied with the 500-to-1 ratio of paper ounces versus the ounces that actually exist.

David: This is a topic that we were talking a lot about in 2007 and 2008 when we launched the Commentary, Kevin. It was that the 19th century belonged to the British, the 20th century belonged to America, and the 21st century belongs to Asia, to some degree.

Kevin: Who had the gold in all three of those occasions?

David: And that is why I mention it because, as my dad used to say – this was one of those breakfast table conversations – “He who own the gold makes the rules.” So, today, you see a gradual shift of gold, tomorrow you see a gradual shift of political power that follows the money and the economic influence. And so it is a gradual thing, but we wake up in 2035 or 2040 and we wonder what happened, and those shifts are so slow as to be imperceptible to us who care about what happens on a day-to-day basis, but actually, something monumental and tectonic was occurring.

Kevin: Dave, since the 1980s when I first started here, I have imagined, if I ever were an author, and I’m really not an author, I would love to write a book from a one-ounce gold perspective throughout history, because gold never really is destroyed. It is remelted, it is reconformed. Sort of trace it back from the second chapter of Genesis in the Garden of Eden, through David and Solomon’s kingdom, and moving through Babylon. And then, of course, through the Greek/Roman empire, and ultimately coming into the 20th century.

David: The only chapter I would not like is the chapter where I was converted into the golden toilet seat in Saddam Hussein’s palace.

Kevin: So, you had to go to the bad place?

David: (laughs)

Kevin: Okay, since we are going to go to the bad place, let’s go back to stocks. Okay, sell in May.

David: Right, back to equities. You generally have an optimistic first quarter, and when your corporate executives are talking about their prospects for the year, they look at their full year earnings expectations and they are very, very enthusiastic to start the year. That kind of sets the tone, but it also plays into that part of sell in May, that adage, because it is all too common for executives to hope for the best early in the year and then have to adjust to reality throughout the year if need be.

Very rarely do you find a management team who, in the first quarter, gets out in front of a slow patch and acts as a herald, because what that would do is really cause them problems in management of the business, the raising of capital, increasing their cost of capital, and sending investors fleeing. So you want to start the year with the best news possible and then kind of adjust to reality from there forward. But it is why kind of the best is in by the time you get to this May period.

Kevin: I have a question. Not all of our guests get it right all of the time. They are human. Russell Napier, early in the year, when we saw the momentum that was coming into this Trumptopia, I call it – it is almost a Utopia mentality with Trump – Napier predicted a much higher dollar price, and we haven’t seen that yet. In fact, Trump is down-talking the dollar right now. That seems to be helping gold a little bit, doesn’t it?

David: I think there are some things that are supportive in the short run, but not necessarily defining for the trend. Last week, Trump jumps on that bandwagon, weak dollar comments. And again, supportive, and certainly maybe boost by a few dollars or a percent, but they are not defining.

Kevin: How about the conflicts in North Korea, Syria, Afghanistan?

David: A fair question, but I still think you have the missile strikes and the bombs dropping. These are tension-creators, which are good for a few days of movement in the metal price.

Kevin: But people aren’t panicking yet, are they?

David: No, and it is raw fear. When you are talking about geopolitically influenced moves, really geopolitically influenced moves, it is raw fear that drives the price of gold higher. And we don’t have that. Concern is different than fear. I look at the move from $1050 to $1275, going back to December of 2015 to more recent numbers, and it has been predicated on buyers searching for value and finding it in the price of gold. So, most other assets are priced to perfection. You have stocks and bonds which have ridden an eight-year wave of increase. Basically, what you are talking about is low rates which have continued to embolden risk-takers to the point of amnesia.

Kevin: Aren’t we getting close to a record on stock market rising years? We are eight or nine years into this.

David: Yes, as of March 9th we entered the 9th year of stock market increases. That is long in the tooth by any measure. Not only are we on borrowed time, but it is dependent on borrowed money, and at very low rates. So I think any thinking humanoid would look and say, “Um, raising rates? What does this do to change the equation?” To me, it is fairly obvious. If the equation has been dependent on cheap money to this point, and you are now making the cost of capital rise, you have to change the result. The result in the equation changes.

Kevin: All eyes have been on the stock market. We will sound like a broken record on this because people are still talking about stocks more than they are gold and silver. But silver has out-performed the stock markets, and gold has, as well.

David: Let’s say, at least 12% for silver. That would put it in sort of a top performer class.

Kevin: Just since the beginning of the year.

David: Gold is doing well, up over 11% compared to equities. They have been out-performing all of the indices, even NASDAQ, which, with taking a few points off in the last week or so, is up still around 8%. It takes missiles, and it takes bombs dropping, for anyone in the news media to ask the question about gold. I was on a radio interview earlier this week and the host, with a very critical tone, described gold’s performance as disappointing. And I thought to myself, “Wait a minute. What context? What timeframe? What are you talking about? The bombs fly and it is not up $150 an ounce, it is not a hedge against political or geopolitical uncertainty. What gives?” That was basically the question.

Okay, so it’s true. It is only up 2% since the missiles flew, and last week a big bomb was dropped in Afghanistan. But the bigger picture is the bigger deal. You have the 65-week moving average which has been rising since January and is now moving substantively higher each week to the current level around $1254. And that moving average has long indicated whatever the trend is in play, whether it is a long-term uptrend or a long-term downtrend.

Kevin: We talked about an analogy, Dave, of how long it takes to turn, or to stop, one of those big oil tanker ships. And it can take five miles to stop one of those things, or to begin turning one of those. The 65-week moving average is like that tanker.

David: It took about 18 months for the moving average to turn down, so the price peaked in 2011 late in the year, and yet, the moving average didn’t roll over and start moving down until 2013.

Kevin: But once it does, you have the momentum for years sometimes.

David: Unfortunately. Or in this case, fortunately, because here we have the price reaching a low December 2015, and the price has been rising since. Only did the moving average begin to move up January of this year, so it took about a year for it to turn. It is an indication of a long-term trend.

Kevin: So we are at $1254 on the moving average, which sometimes really serves as a nice floor if there are market moves up and down, right?

David: That’s right. So, there is plenty of volatility that exists between here and the moving average moving past $1900 on the ounce price, but I think the moving averages are, at this point, supportive to the case of the secular trend in gold and silver re-emerging. So, we have the history of markets, which seem to be moving from a lack of imagination for what can be, to imagination on steroids. Again, you look at the sentiment in the gold market. People don’t have an imagination for it moving higher. People do have an imagination for the stock market going to the moon. You juxtapose those two things and see how radical it can be because 2008 and 2009, the baby was going out with the bath water, nobody wanted to own stocks, and everyone wanted to own gold. We have shifted sentiment. Now you can’t imagine anything other than what is in play.

Kevin: You are talking about American sentiment only. We sometimes can be very cloistered in the way we think, but if you look at the rest of the world, gold import numbers are up, not only for China – you discussed that last week – but they are up for India, they are up for Russia. Even the central banks right now are net buyers of gold.

David: That’s right. Following the Modi monetary debacle last year, gold import numbers in India have picked up again. I’m still reading reports of limited cash availability within the economy, people going to ATMs and it is kind of a one-in-ten crapshoot, if there is any money, at all, available. We mentioned recently that following the restrictions, the increased fees for gold imports into India, normal consumption through the normal channels has returned. And on top of that, if you look on a broader basis, central bank accumulation around the world, and particularly in the emerging markets, continues.

And it is not one part of the world, it is the globe, not at the feverish levels we had a few years ago, but still well above the trends of more than a decade ago, when they were, in fact, dumping the asset, treating it as worthless. Quite the opposite is true today. You have accumulation, which is the trend. That leaves us with, really, the compelling case for the investor. The investor is the swing vote in the gold market. So, give the average investor a reason, any reason, to own the asset, and a lot of progress in price is made, because you are talking about the directional trend of price being made at the margins, and if the investor is that swing vote, very little buying at the margins has a big impact on price.

Kevin: Dave, as long as I have known you, you have this unique ability to scout around and say, “What is the trend, and now, are there still any laggards? Is there any opportunity in the trend?” I remember even when we went to Argentina a couple of years ago, we went into this little wine shop, and you were looking for a deal on, not a cheap bottle of Malbec, but you wanted a deal on it. I remember how you talked to the owner, scouted it out. You ended up buying a very nice bottle of Malbec for a much better price than probably you could have gotten anywhere else. So, you scout these things out. In fact, I have even known you to wear shoes that are two sizes too small because you got a good deal on them.

David: (laughs)

Kevin: But we’re not going to go there. Your pain wasn’t really your gain in that particularly case. But gold imports are up. Everyone is interested in gold worldwide. No one is interested in gold in the United States. Is there some way for us to capitalize on something that is undervalued in that case?

David: Yes, I just want to set the record straight, that the pair of cycling shoes that I bought that were two sizes two small, I was on a very different budget when I was 18, and it just made all the sense in the world.

Kevin: (laughs)

David: That was many years ago, and buying quality at a very reasonable price, and being able to endure more pain than most, yes, that sort of fits the 18-year-old profile. I hope that I am not such a sucker for a deal anymore.

To your point, the buyers today are still predominantly outside of the United States. This has opened a very unique opportunity. Once in a blue moon you have the premiums on U.S. product – I’m talking about the older U.S. $20 gold pieces. They get crushed by lack of demand. And because of the size of that market, the premiums above the raw gold value can swing from extreme under-valuation to extreme over-valuation.

Kevin: Because it is a very small market. And when people want it, they want it. And when they don’t want it, you can’t give it away.

David: It is actually a very healthy indicator as to who is buying what and where, because you have very low volumes coming into the gold market here in the United States, but that is not true if you are talking about a European space where they are still worried about zero interest rates or conflict between Asia, potential economic issues relating to the French election, which is just coming up in the next few weeks. There is a variety of reasons why Europeans look at gold, and they’re buying it. There is a variety of reasons why Asians look at gold, and are buying it. There is a variety of reasons why it is not being bought here, and I think the chief reason among them is the Dow-Jones Industrial Average is near all-times highs.

But again, going back to these premiums, premiums are at a very low level presently, and in my opinion, they offer a compelling value play. I have moved out of most bullion gold into that kind of product for the purpose – and there is a real strategy here – for the purpose of repositioning back into bullion.

Kevin: With more ounces, basically.

David: Right, when the premiums are higher, taking the added premium value and buying more gold with it.

Kevin: Why don’t you answer, for the listener, what actually triggers an increase in premiums, because we have been through an amazing increase. Just since 1987, since I have been here, I have seen it a number of times where the premium can skyrocket, not just a few percent, but hundreds of percent.

David: Yes, and it happens as a consequence of the U.S. buyer returning to the gold market. Prices are cyclical in all assets. Just keep this in mind. You need to understand this as an investor. Prices are cyclical in all assets. Knowing where you are in the cycle helps tremendously, which is why as insiders in the gold market, this is kind of a no-brainer for us. What I am doing is turning a static gold position into a dynamic one. I want to capture the premium on those coins over the next few years and turn it into more ounces. These are free ounces. Having an ounce-generating strategy in play is helpful when you are waiting for the prices to improve.

Kevin: You haven’t just done this with rare coins. You have done this with various types of silver, you have done it with platinum and palladium.

David: Let me clarify one thing. Even though they are in the category of rare coins, we are talking about something that is semi-rare, because we are not talking about something that is completely esoteric, and for two collectors on the planet, and only those two are willing to bid it up. We are talking about something that is far more commoditized – common date, U.S. 20s – that is really the sweet spot because you have liquidity along with this advantage of, not only premium appreciation, but also price action given the metal itself.

But you are right, I have done the same thing on a smaller scale with silver – with junk silver. Three times in the last ten years I have considerably grown my silver position in ounces because the premiums on the bags increases, and if I can buy it at less than 5%, and I can sell it at between 12%, 17%, 20%, 30% over the silver price, guess what I’m doing? I’m taking those premium dollars, putting them into the most generic silver position possible, and I end up with a bunch of free silver. And then as soon as the premiums on the bags dissipates, I go right back into the bags, reload, and I’m ready for that again.

Kevin: And you compound ounces every time you do that.

David: That’s right.

Kevin: But you’re looking for a value different than most people look for. Most people are looking at dollars and cents when they are looking for value, but you look at value relative to other things.

David: Right, I think many investors view value as the price that you pay. And I think certainly Amazon and Walmart reinforce that as a mindset, as a certain cultural trend. And I want to challenge that with the notion of value being what you get for what you pay. And having been in the precious metals market for nearly 50 years as a family, we have learned a few things that add tremendous value in the context of a consultative relationship.

Kevin: But you are also careful to look at proper portfolio representation in the various assets.

David: That is where it begins. If you have proper portfolio construction on the front end – it is one thing to pick who has the cheapest price on a krugerrand or a Silver Eagle. That’s fine. If what you want is a static portfolio in gold ounce exposure, perfect. I don’t criticize that one bit. But you are choosing static versus dynamic and you don’t have the ability to compound your ounces.

Kevin: There is one thing that can rise. It is the gold price, or what have you. But when you have something in this older form of coin you have a double play.

David: Right. And I mean, by older coin, again, if we are talking gold, we are talking $20 gold pieces and things like that. If we are talking silver – this is pre 1964 dimes, quarters and 50-cent pieces.

Kevin: Or the silver dollars that your grandma gave you.

David: This is not esoteric, it is just finite. And because it is finite, it is subject to exaggerated rules of supply and demand. So, ultimately, the gold market is the same thing – subject to the rules of supply and demand. If investors come in and buy more than is available, then the price goes up. We are talking about a subset to the gold market which is smaller in size, and the moves in price are more exaggerated.

So, that is what we are talking about in terms of a double play. Proper portfolio construction – what do you want? If you want a static portfolio, the ignore this. If you want a dynamic portfolio, built in, that gives you a double play, a play on price, and a play on relative scarcity which feeds premium increases and decreases – guess what? That volatility is your friend. And if you like free gold and silver, that is what you have to build into a dynamic portfolio.

Kevin: So that is where the new dollars needs to be coming in.

David: If I were putting new dollars into the market, I think certainly bullion is a good option, yet it lacks the dynamic we just described. It is a one-dimensional play on price. Again, if that is what you are looking for, great. Ultimately, we are talking about a play on scarcity on both of these. Bullion is just a larger pool to play in. As an industry insider, I am always looking at ways to maximize my own portfolio allocations in the metals, and we have seen these premium swings occur many times over five decades of business.

Kevin: But people are distracted right now, Dave. They are looking the other direction. This is why those prices are so low. They are looking at the stock market and saying, “Hey, did you see?”

David: Yes, the U.S. investor is completely enamored with the U.S. stock market for the present, and I think that love affair basically captures all or most of the investing public’s bandwidth. They don’t have space to think about – and quite frankly, there is a lot of positive optimism relating to Trump. “Hey, Trump is going to fix the world. He is going to make it a peaceful place. Everything is going to be better. The economy is going to grow forever and ever and ever.” And you know what he represents? He represents a change from what we had for the last eight years. So I can appreciate there being a sense of relief. Now, having a sense of relief is an emotional experience. Let’s acknowledge that an emotional experience is, and can be, different than practical reality. We still have to see which of his proposals will be put through the legislative process, which of his proposals he forces through by executive order stand in the courts. So, it is not as easy as being starry-eyed and saying, “I’m going to change everything for the better.” You still have to deal with the morass which is our capital city back on the East Coast. So, again, the love affair that people have with the stock market – I think it has them blinded to the opportunity which we look at. It is an opportunity for someone who is willing to ask the question about the market consequences of a lopsided bet. When everyone is piling into one asset class with one particular perspective, you are going to find other pockets which are completely neglected. Gold is neglected in the U.S. You said it. Gold is not neglected overseas, but it is being neglected in the U.S. And as a consequence, U.S. products, like the American $5, $10, $20 gold pieces are exaggeratedly cheap, because again, when one asset class is getting the attention, another is neglected, and that, my friend, is the domain of a value investor – looking for the neglected, looking for, perhaps, the hidden beauty.

Kevin: Let me play the other side of this, though. Let me be the skeptic here. Is there a possibility that the current circumstance remains the case, in other words, the premiums just never come back.

David: (laughs) Yes, that is a possibility. If the stock market continues to capture the imagination of the American investor indefinitely, then within the U.S. market gold will remain neglected, and the pocket of value I am describing is going to remain too cheap – a lot longer.

Kevin: So the question is, how high can the stock market go?

David: Well, there you have it. The question is not only, how high can U.S. equities go, but how long can they remain at over-valued levels? We have already said that the margin time bomb is already ticking. 528 billion dollars, as a percentage of stock market capitalization, as a percentage of GDP, or just in nominal terms on all three measures…

Kevin: That’s borrowed money.

David: To get a comparison back to every other peak in stock market history, we have blown them all out. So you have more borrowed money today in the stock market than you had as a percentage of stock market capitalization, even in 1929.

Kevin: And every time it got to this level, or it hasn’t gotten to this level, it was lower than this, it always crashed.

David: You’re paying interest on half a trillion dollars! So the reality is, that has to be unwound. And so, we do have a certain timeframe in mind. What is the timeframe? How long can it last? That is really a question for psychologists. It is really a question for sociologists. I remember the scientist’s befuddlement – was it Isaac Newton who was describing the manic behavior of the markets? “I can calculate the motion of heavenly bodies,” which you, in fact like to do (laughs), “but not the madness of people.”

Kevin: It is frustrating for mathematicians. This is why the Federal Reserve people act like they have really got this thing figured out, because they are mathematicians. So, let’s go back to a little bit of solid value math, Dave. You have always talked about the Dow-to-gold ratio as a great way to see whether the Dow is over-valued, or gold is under-valued, or vice-versa. Just review that again.

David: We have always put the context for a Dow-to-gold ratio at 5-to-1, 4-to-1, 3-to-1, that context being driven by economic concerns. And historically, that has been the case. You get to those levels on the basis of the math involved, on the basis of economic and financial problems. But for the ratio to collapse to a 1-to-1 level, geopolitics has to be in the frame, in our opinion.

Kevin: And that is a great point, because back when we had the 1-to-1 ratio last time, that was 1979, that was the invasion of Afghanistan by Russia. It was geopolitical event.

David: It was a geopolitical event because everybody in Saudi Arabia, everyone in the Middle East, though to themselves, “We’re getting ready to lose access to black gold, we’d better have the real stuff, and ship it to Switzerland, because if we don’t have real gold and we don’t have access to our oil money, we’re doomed. How do we maintain a 50-million dollar annual budget?”

Kevin: (laughs)

David: Tough lifestyle.

Kevin: Yes, and it is probably 100 or 150 million now, annual budget. So 5-to-1, 4-to-1, 3-to-1, relative. So three ounces of gold buying the Dow. That is a reasonable rate to get to, even without some sort of large geopolitical event.

David: Right. There has to be a level of concern that drives simultaneous liquidation of risk assets like stocks, and the accumulation of safe have assets like gold, to a level where prices simply don’t matter. What do I mean by prices don’t matter? On the one side of the equation, you have stock investors who don’t want to own anymore, and they are saying, “Just get me out. I don’t care what the price is, just get me out. It doesn’t matter what the bid is, just get me out.” And on the other side of the equation, it is, “Just get me in.” And we have seen it. We have had millions and millions of dollars wired to us in a single day where people are in queue for whatever product is available. “Just get me in, just get me in, just get me in.” We know what the manic stage of a gold bull market looks like and it did not occur in 2008, 2009, 2010 and 2011. It did not occur. I repeat, it did not occur. We have been around long enough to know what it looks like and feels like, and there is psychology and sociology involved. What I am suggesting is that when you survey the geopolitical landscape…

Kevin: Yes, let me do a Rorschach test of geopolitical landscape right now, of potential problems that could drive us to a 1-to-1. Let me just throw something out. Syria, Iran, Russia, China, North Korea, Turkey – even the European continent.

David: Right. Turkey, you have the dictatorial powers which were granted to Erdogan over the weekend. That is kind of significant. You have the French election, which may change Brexit to Frexit, and completely implode the Frankenstein, which is what Ian McAvity called the euro, which was the mishmash of currencies melding together – franc and stein – get it? Germany?

Kevin: Good play on words.

David: He was always good at that. You’re right, the Middle East is just a grand cluster. You have Syria, Iran – those are in the front pages today, but it could be any number of countries tomorrow. I think you have a reasonable number of possible – let’s call them risk, or force, multipliers. I can’t tell you which geography will move to front and center, which will be in the limelight, which will be the mother of all concerns.

But here is what we do have today. Here is what we know we have in the pipeline. The mother of all debt problems is already here. And the mother of all geopolitical conflicts, very interestingly, may not be far behind it.