Podcast: Play in new window

- Social Control Is a Major Goal Of CBDC

- FDIC Has As Much Money As Warren Buffett & No More!

Big Brother to “Solve” Dollar Crises with Fedcoin

March 29, 2023

“What we’ve seen over the last decade is, crisis opens the door to opportunism. There is no honest reflection. No politician takes ownership of their policy mistakes. And so, the solutions that are offered are ways that you can, in this case, control bank risk, control depositor flight, and control investor behavior, and all of those things are best accomplished both here in the US and universally using a central bank digital currency.” — David McAlvany

Kevin: Welcome to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany.

I remember your dad when he would get up and talk, he would remember that the communists, I can’t remember which leader. It might have been Lenin, it might have been Stalin. They said, “You know what we’re going to do? We’re going to sell the rope to the capitalists in which they will hang themselves.” I can’t help but think about all these crisis quotes that we’re having right now, banking crisis leading to a currency crisis. I just wonder if the people are going to cry out for the rope in which they’ll be hung, which is maybe the central bank digital currency. What are your thoughts, Dave?

David: Yeah. Well, that takes us to the end game, a crisis of confidence on the one hand might open the door to a rethink of our monetary system. And some have suggested—Lewis Lehrman, very famously—that there is a path back to the gold standard. And maybe we have an open mind to that on the other side of crisis. Perhaps that case becomes more obvious to the public as a crisis unfolds, like the Weimar crisis and many others in recent centuries as it just grinds on. But the modern playbook is one of crisis opening the door to opportunism, not really honest reflection and ownership of the mistakes being made from a policy standpoint—to better control bank risk, to address depositor flight, to deal with investor behavior. Kevin, we’re on the threshold of universal central bank digital currencies, and there’s implications for that in the precious metals market. I think those implications are huge.

Kevin: I just wonder about that opportunism, too. There’s opportunism in trading behavior, people who are just trying to make a profit. Then, of course, there’s opportunism, when you’ve got a group of people that would like to control other people, the last thing they would ever want to do is have a gold standard. My gosh, gold would probably be the solution, but it doesn’t allow social control, does it?

David: I love Lehrman’s ideas. I agree with him, in terms of the ease with which we could go back to one. The one thing that stands in the way is the political will to do it. Certainly from the standpoint of politicians, put that as a low probability event because you have to concede so much in terms of managing your country like you might have to manage your household. Imagine staying within a budget. Can you imagine? Well, that’s not something that they want to imagine. That seems like a very dark world.

Gold prices rose substantially over the past two weeks as the banking system was on the fritz. Silver outpaced the yellow metal, and in that context, the gold/silver ratio contracted slightly. Speculators, of course, are the ones that drive short-term trends in any market, and in this case, speculators added an element of temporary satisfaction. Gold and silver prices were higher, gold and silver investors are happier, but a lot of the activity was in the futures market.

What the futures markets give today, they take away tomorrow, and as fast as concerns about regional banks dissipate, so, too, is that metals trade there just for the moment. It gets reversed. So, futures trading this week, you had leveraged speculators who were selling crude oil, selling gasoline futures, buying precious metals. You had long positions in both metals, gold and silver, which saw net increases. Speculators primarily—this is managed money—adding 6,000 contracts, and then you had the short positions which were cut by 14,000 contracts.

But, Kevin, more critical than the daily transactional noise is the fact that we are flirting with breakout levels which are going to surprise the average investor and the average trader. I suspect sometime later this year a breakout to new all-time highs in gold. And the more important players than those speculators we were talking about in the futures market are your long-term investors and the folks that position themselves with more of a business mindset—your commercial interests, hedging production, the stickier trades, whether it’s institutions, individual investors, family offices, less of the hot money crowd that’s just in today and out tomorrow.

Kevin: You talk about opportunists, and that’s true. You’ve got that hot money crowd. They look at gold like they look at soybeans or sugar or stocks or NASDAQ. The idea is, let’s just get in long enough to make some money, get out before it falls. But what you’re talking about on the longer-term investor, that really is the great motivator for gold. It’s so different than other investments because other investments, you do buy to make money. Gold has that amazing power to preserve buying power in a crisis, but that goes to stock sentiment right now. What are people thinking when you look at the stock market? Are they taking the downturn in the economy seriously right now or are they still just speculating?

David: The hope is that the worst is behind us, that 2022 marked an inflection point as we got to the end of that year, and perhaps going forward we’re in a much, much better place. So, as far as sentiment is concerned, since the all-time highs were put in 15 months ago in the NASDAQ, we have not had one single day of capitulation. You measure capitulation as a ratio. This is math. This is not just something we pull from the sky. It’s a ratio of up versus down volume, and day of capitulation is where that ratio is one to nine, where your up volume is one part to the nine parts of down volume. We haven’t had one day, not one day. We’re indebted to Alan Newman for the insight on those capitulation numbers.

Stubborn optimism is what you see in the marketplace today. Far, far from capitulation, which is the psychological marks of a low in the market. In the marketplace, where sentiment is a tell for where you are in the longer-term cycle of those decisions being made by investors, it helps us. It helps us know that we’re not through the bear market yet. Sentiment would suggest that we have further to go because sentiment is still fairly strong, and frankly, that optimism can be misplaced. It can be dangerous.

Valuations are another way of looking at the market. They complement sentiment. Valuations also suggest that this optimism is misplaced.

After broad-based losses last year, the Shiller PE—this goes back to the price-earnings multiple—if you’re smoothing it out, adjusting it over a 10-year period, 10-year rolling average of the PE, it remains 68% above its mean, 78% above its median. In the nature of full cycles going from market peaks to the ultimate troughs, they never come close to simply stopping at the mean or median evaluations. Instead, where do you go? You swing well below those levels. Sometimes the average retail and even professional investor has a hard time fathoming just how low markets can go on the downside. So, from valuation perspective, things are still expensive.

Kevin: And I sometimes have to think in very simple terms on that Shiller PE. If a business earns $100,000 a year, and somebody comes up and buys it for a million bucks, in a way that’s a 10 to one price-earnings ratio. The earnings is $100,000. The value of the shares, of the value of the business, is a million bucks. So, what you’re saying is, above that Shiller PE right now, we still sit 68% above the mean, 78% above the median. And when have we not seen that settle back down, at least to the mean and the median? And what you’re saying, it goes below that before it’s all finished. So, where does the stock market go from here?

David: Yeah, small and mid-caps are still under more pressure than the NASDAQ. The NASDAQ has had some relief here in the last few, I’d say 10 days to two weeks certainly, and since the beginning of the year there’s been some relief for NASDAQ. But the idea, the notion that rate hikes are nearly done—and again, we come back to this word hope—people are hoping that we’ve made our way through the interest rate hike cycle. The pivot is nearly here, and on that basis, you’ve had a lot of activity in technology shares. The Dow is not as strong. Neither is the S&P, though it gets a little bit more of a boost from the big tech components. But really, we’ve got negative returns for the Dow year to date. Positive returns, which have barely put back even half of the losses from last year in NASDAQ. And I think those are actually pretty precariously placed.

Kevin: And there are two things that can affect price/earnings ratio. If you had a huge increase in earnings, that would bring that price/earnings ratio down in a way that didn’t hurt. Or the other side of that is the shares have to fall. So, what are we looking at right now? If we face recessionary pressures, do we see earnings rising?

David: Well, the consensus—and keep in mind, Wall Street takes a straw poll on a lot of these things. What’s going to happen as we get towards the end of the year? What do we think the next quarter’s going to be? You get all the economists together and they pool their “wisdom.” Maybe it’s pooling ignorance. But consensus S&P earnings are for there to be a steady increase each quarter all the way through year-end. We start the first quarter at $51, is the estimate, we gradually rise to over $58 on the quarterly S&P earnings estimates. And curiously, this is supposed to take place in the same time where consensus estimates for GDP growth, just general economic growth, are contracting. First quarter starts at 1.5%. Shrinking to two-tenths of a percent in the fourth quarter. Doesn’t make sense to me.

Kevin: Well, and that’s what I’m wondering. If the GDP is shrinking, how are earnings going to improve? In the long run, sometimes it does help to have a little bit of shrink. We’ve talked to Tomas Sedlacek, who believes that you shouldn’t just bow to the idol of perpetual growth. So, shrink does not hurt. I was talking to my wife the other day about the depression that most people don’t remember back in 1921 and 1922. Remember, you interviewed Jim Grant about that. They let everything just go. They didn’t add money to the economy. They didn’t have a blanket bailout for the economy. We just went through a depression. Everything came out a little bit stronger, and then we had the roaring ’20s after that. And so, if economic activity slows, let’s look at quantitative tightening. That’s what they were trying to do was slow the economy. Do you think this banking crisis, what’s going on right now, is actually accomplishing that without having to tighten?

David: What a fascinating story that was, the forgotten depression of 1921. The governmental response was not to increase spending. We weren’t addicted to bad, really stupid Keynesian ideas. And what did the government do to resolve being in the midst of a crisis? Rather than stimulate demand by spending, they cut spending by 50%. They cut spending by 50%. Unemployment increased for less than six months, and the economy very quickly recovered.

It was strong medicine. It was hard medicine. It meant that they embraced ambiguity and they embraced the unknown. Something that we cannot do today. We are not willing to say yes to the unknown outcomes. So, what do we do? We grasp for control, and we try to stimulate demand, being willing to spend an infinite number of dollars to prevent a recession, a depression, or what have you.

So, do I think economic activity slows while earnings improve? I think that’s actually reasonable that we see a reduction in both. While there may be a bit of margin recaptured as we move throughout this year, again, keep in mind, inflation numbers are not officially, in any ways, they’re not as high as they were last year. So your year-over-year comparisons will factor into reduced inflationary pressures. Having said that, inflation hasn’t disappeared. The larger concern as we march towards year-end does come still from the banking sector. Yes, there are the liquidity issues of last week, but to a large degree, those have been filled by the Federal Reserve and the Federal Home Loan Bank stepping in as lender of last resort, filling that function.

Federal Reserve assets have grown 392 billion in two weeks. That gives up over 60% of the ground gained through the last nine months of QT, quantitative tightening. QE is at least temporarily back. And by the way, the gold market has noticed. So, you also had the Federal Home Loan Bank pumping 304 billion in liquidity to the banking system. So, the tally thus far, just shy of $700 billion to calm nerves, and I’m glad it’s nothing more serious than a few small regional banks. And, of course, they’re saying, “Oh, they were terribly run.” I’d hate to see a larger bank— Again, 700 billion to calm the nerves? Amazing.

Kevin: Think about this, Dave. If a person knows that no matter what they do they’re guaranteed to get their money back. What it reminds me of, my daughter’s got one of these blankets that’s ultra-heavy, that when you lay under it, it gives you an additional degree of security. There’s something about it where it’s like— You’ve probably seen those weighted blankets. What we’re talking about at this point is a moral hazard blanket bailout of everything. How does this play out going forward?

David: So, perhaps we’ve got the liquidity and the solvency concerns being allayed if you just pump a bunch of money into the system and make sure that the bank’s never going to run out. And actually, the 620 billion in unrealized losses, there’s estimates as high as 2 trillion.

The moral hazard card, it’s been played. And you can see Janet Yellen equivocate on the degree to which all bank deposits will be covered, implicitly covered, or just some, or just some banks of some size.

The real issue that has us concerned going into the end of the year is that of tightened financial conditions. Last year, we had robust bank lending, and you’ve got a much more challenging set of conditions this year. If credit growth is required in the modern age to drive economic growth— This comes back to what you were saying about Tomas Sedlacek and the notion that we have to have growth and so we’ll do anything for it, including drawing tomorrow’s growth into the present. That’s what debt does is it spends tomorrow’s dollars today. So, you’re just robbing tomorrow’s growth and getting the benefit of seeing it here and now.

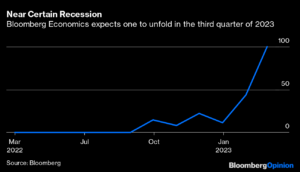

So, if credit growth is required in the modern age to drive economic growth, and bank credit was a significant component in 2022, wouldn’t it be safe to assume that the deterioration in the banking sector in the first quarter this year is likely to materially tighten lending standards, and therefore loan growth, as the year proceeds? The net effect of reduced bank lending is a reduction in economic activity. To come full circle, you’ve got an issue with a few banks. Maybe that turns into an issue with a lot of banks. But we’ve already set in motion tightened financial conditions throughout the remainder of this year, and it’s basically sealed the fate that we do have a recession. The question is how big and how bad is it?

Kevin: Last week, you interviewed Doug Noland, and that was a great interview. I would recommend our listeners who missed that to go back, and if you heard it, go listen again. But Doug has always been concerned about the final straw. And the final straw is the people who are bailing out no longer have someone to bail them out. The government’s the last resort. The only tool the government really has is the value of the dollar. If there’s no dollar, then there’s no government to bail out.

David: Well, Doug’s comments over the weekend in the Credit Bubble Bulletin were on target. The market’s fixation on Yellen’s deposit guarantee comments suggests a deep concern for bank-run contagion. And while moral hazard is an issue, he says that I am today more concerned about the fiscal consequences of blanket deposit guarantees. I’ve argued that the global government finance bubble is the end of the line. There’s no new source of credit growth that will let central banks and governments off the hook, and it doesn’t take a wild imagination right now to envisage simultaneous uncontrolled expansions of Fed liabilities and Treasury debt.

Kevin: The whole idea of being able to pay off any problem or solve any problem at a price, at some point, the price is too high. You don’t have the money to pay it.

David: That’s what’s in play, isn’t it? You can solve almost any problem. It’s just a question of what’s it going to cost to do it. And so, Doug’s pointing to the credit bubble end game, we’re playing with the confidence, not of retail bank depositors. And the bigger picture here, if you think that this is about a few retail banks and a few dollars in the banking system, you’re mistaken. Ultimately, we’re talking about the confidence of the global government bond investor. So, maybe today we’re talking about 700 billion of liquidity coming into the bank system, but we’re really anticipating the 3 to 5 trillion dollars tomorrow. The real risk is not a run on banks. That’s small potatoes compared to a run on the dollar and other major currencies.

Kevin: All I can do is think of this hot money concept now, not applied just to banks. We talked about hot money not being loyal money. This is money that can flee. It used to be, you had to go down to the bank to do it. That’s what a bank run was. You’d see these pictures of long lines of people. And in fact, my mother-in-law called me and she said, “They’ve closed the drive-through at my bank because they don’t want the appearance of a bank run.” But these days, you don’t need to drive through. These days, you don’t need to go see the teller. All you have to do is pick up your phone and exit. But what happens, Dave, when it’s no longer just a bank run on cell phones where people are moving from bank to bank, but it’s a bank run on the currency itself?

David: Well, it’s fascinating. Bill King, who’s often a guest on our program, commented on this in recent days. He said, “I remember the crisis in 1987. When the stock market collapsed, there was a circuit breaker.” The circuit breaker was you had to call your broker to sell your shares, and if you got a busy signal, you just had to try back. And so you tried and you tried and you tried, and maybe you didn’t get through. But there was a natural constraint, just like there’s a natural constraint with a bank run in the old days where you had to get in queue and they could help you one at a time until they ran out of money.

In the modern day of digital money and digital deposits, coming back to the banks, we’ve got a fresh look at bank stability and how banks are now having to look at the stability of their deposit bases, realizing just how fast digital banking can affect deposits. There is no circuit breaker. You want access? You’ve got it instantly. There’s no one that says, “Just wait in the queue” or “we’ll get to your phone call as and when we can.” How much will that factor alone give pause, as we come into the end of the year, to longer-term lending, as banks look at their deposits and say,” Ooh, wait a minute.”

You had a group of JP Morgan analysts comment this week that the uncertainty generated by deposit movements could cause banks to become more cautious on lending. Then you also had Jane Fraser, CEO of Citibank, reflecting on digital dollar deposits, and she said, “It’s a complete game-changer from what we’ve seen before. There was a couple of tweets, and then this thing went down much faster than has happened in history.”

So, our concept of bank stability and deposit stability, and really, I mean, what happens when something like this takes place when all of your Robinhood yodelers or HODLers [hold on for dear life] or whatever they call themselves are looking to exit every position on the stock market? Where’s your circuit breakers? You don’t have them. The safety built into this arcane analog system back in the ’80s doesn’t exist today. This is digital, baby! It’s digital!

Kevin: Yeah. Where’s the friction? Let’s face it. I feel for the bankers, in a way, because they’re sitting there with 30-year Treasurys—these securities portfolios. We’ve been giving a lot of bank ratings to people, and they’re calling us and they’re saying, “Hey, what’s the rating of my bank?” And it’s like: well, it hardly matters. Let’s look at how many securities they’re holding because you’ve got instant liquidity, like you were talking about with the digital age. But the things that the banks are invested in aren’t instantly liquid, not even close.

David: And long-term Treasurys are probably more to the tune of 20 years, and there’s a mix of mortgage-backed securities in there, and those certainly stretch to 30 years. But we have temporary balance sheet reprieve with the securities portfolios we discussed last week and in the weeks previous. Prices have bounced. Yields have eased a bit for now.

So, really, the second shoe to drop in the banking sector as we move through 2023 is a different part of their balance sheet. The securities piece we looked at before—mortgage-backed securities and Treasurys. But they’ve also got their commercial real estate loan book. The Wall Street Journal reports smaller banks holding around $2.3 trillion in commercial real estate debt, 2.3 trillion in commercial debt. I’ve seen two different numbers, 80% of the market held by small banks, 68% is the other statistic that I’ve seen. So, I guess it depends on how you define a small bank, but there’s more pressure building there.

You’ve got approximately $400 billion in loans that come due this year, and an additional 500 billion is, again, this is out of 2.3 trillion. So, you basically had half of that market rolling over in the next 24 months, and that’s pretty significant. That is a lot of pressure on commercial property owners. You have to ask yourself the question, what will the terms look like when you go to refinance? Will terms, in some case, even be on offer? And don’t forget, there’s been some really complex shifts within the commercial real estate market coming through Covid, where bankers are now looking through a very different lens at that part of their loan portfolio.

And, of course, overall financial conditions tighten. We already have that in motion. Stress from the commercial real estate side of their portfolio only further tightens financial conditions. These are some areas of weakness to watch carefully.

Kevin: Dave, I think sometimes we can’t imagine bank loans as a percentage of overall GDP, just how large we are. And I saw a chart recently, I think you’re going to attach it to the Commentary, that shows that, as a percent of GDP, bank loans that are outstanding, we’re about on par with Russia, but there are countries— This is not just a United States problem, this is a worldwide problem. In fact, I wonder if Europe and some of these other places have even a greater problem going forward.

David: Some of the crises that we had within the banks—and even if you’re looking at the international markets—in the ’80s and in the early ’90s in particular, there were a number of international lending crises, and they centered in the banks because banks were, in the US, the dominant lenders. As we got through the ’90s and into the 2000s, the banks took a backseat to the securitization models, the product creation from Wall Street where they started being the issuer of IOUs, and it was not just focused on the banks or primarily focused on the banks. And so, yeah, the chart that you’re talking about illustrates very well the focus that is still in those banks.

And again, the important factor here is that if bank lending slows, reduced bank lending is a reduction in economic activity. Europe and the rest of the world are actually in a far more precarious place than the United States, as bank lending as a percent of GDP is less in the US than in other geographies. That was not the case in the ’80s and ’90s. Bank lending as a percentage of GDP was considerably higher in the ’80s and ’90s for the US. And things have changed. In the show notes, we’ll attach the chart—and this is a chart compliments of Bloomberg opinion writer John Authers.

A global tightening of financial conditions has occurred, with implications not only for US GDP, but for global GDP growth as well. Instability within banks ties directly to whether an institution can keep the confidence of its depositors. Doug Noland and I were discussing this the other day. Regardless of a central bank, regardless of a Treasury, accommodation providing liquidity that a bank may need, like what they’ve done with this bailout program where you can exchange your portfolio for a loan, and you’re getting full credit for the value of the bond, even if it trades at a discount. You’re still getting full credit in terms of collateral. Well, okay, that helps the impaired portfolio holdings as you use it as collateral at full value. But there still is the issue of depositor flight, and this is what Doug brought up in the conversation. Doesn’t matter if your assets are treated as if they’re whole. If money is exiting, you can still lose your banking franchise, forcing the hand of the bank to create liquidity, either use up what little liquidity they have or liquidate assets and shrink the loans outstanding.

It’s just fascinating. It’s really fascinating to see the dynamics that have unfolded in recent weeks, and what that has set in motion where we anticipate it really biting as we move towards the end of the year.

Kevin: And the smaller banks haven’t really hedged the interest rate risk, but the larger banks have, haven’t they?

David: Well, I would say this, the largest banks are required to hedge that interest rate risk, and the smaller banks don’t have the same requirements, but the prudent ones have. And there’s a few imprudent ones that we’re discovering have not, and I think that’s where the messes have been and will continue to be found.

So, how you suss that out, you don’t know. The other issue is not just the interest rates that the largest banks hedge, but they hold the most derivatives. And so, this is something else that we’re going to have to encounter in the months and quarters ahead. On a good day, derivatives are not a bad thing. On a bad day, derivatives are very bad because they create a circumstance in which you can’t calculate your risks. You don’t know where your risks lie, and you don’t know if, at scale, your counterparties are going to be reliable—or maybe you’re the unreliable counterparty in the equation. When people are concerned about those counterparty relational issues due to derivative exposure, depositors have reason to take flight. Such was the case with Credit Suisse last week.

Kevin: You were talking about scale. Sometimes we have a hard time getting the difference between a million, a billion and a trillion. Talk about scale. Credit Suisse. What would that look like—that, and Deutsche Bank? We’re talking trillions and trillions of dollars.

David: Well, in terms of their derivative exposure, for sure. Now, we talked about the portfolios of securities that these banks have, and we also talked about the idea of a blanket guarantee. This goes well beyond what the FDIC can do, but the FDIC is clearly a part of the story. The Treasury blanket guarantee has to be—has to be—a part of this story. At year-end, bank deposits totaled 17.2 trillion in the US. According to SP Global, 7.9 trillion of the 17.2, 7.9 trillion of the 17.2 was uninsured. That’s a lot of potential dollars looking for a safer home, right?

So, the blanket guarantee, which would need congressional approval, keeps everyone happy. Without it, every dollar in excess of the $250,000 FDIC deposit limit is at risk. Can their bank, can your bank, navigate the narrows and come out whole on the other side? This is one of the reasons why we’ve seen money market funds, particularly Treasury money market funds, have a huge influx. Three hundred billion dollars since March 9th has come out of banks and gone into Treasury money market funds. Fifty-two billion to Goldman Sachs, 46 billion to JP Morgan, 37 billion to Fidelity. And again, these are your Treasury money market funds, flight to quality. That’s what you’re seeing. Flight to quality. These are deposits above the 250K. And again, there’s quite a bit of them. 7.9 trillion is how we began the year. That’s huge. It’s huge.

All that to say, there’s a lot more that can flow out of banks and into Treasury funds if there’s a reason to, which is why that blanket policy is so important. Am I for it? No, but what does the world look like without it? Well, that’s a question— Again, we come back to insecurity and how we deal with the unknowns, and that’s where the Fed, the Treasury, they don’t have the stomach for it. They can’t deal with it. I think the average investor would say, “No, we don’t want to find out. We don’t want to find out. We’re just grateful that Grandma Janet’s going to help us there.” And I think ultimately she will. So, it’s a flight to quality, which may very well continue without that blanket guarantee.

And by the way, if you want to focus on the other part of the equation, the FDIC’s total capital, again, so take out the part that’s uninsured, 7.9 trillion. That leaves you with roughly 9.3 trillion in bank deposits that fall under the $250,000 limits. The FDIC’s total capital is $128.2 billion. That covers exactly 1.37% of deposits, 128 billion as a percentage of $9.3 trillion in “insured deposits.” This is no joke. This is no joke. Everything in the financial markets is a confidence game. It works as long as confidence can be maintained, again, which is why you look at how this is played, and it’s theater.

Every day we come in and the markets start up and we get to see who says what and what they’re going to promise and how this problem’s going to be solved and what this opportunity looks like. The insured depositors are not concerned because they’re insured. But clearly, they can’t do the math because to be insured means nothing. Warren Buffet has that exact amount of cash in his hip pocket, 128 billion. Just by coincidence 128 billion happens to be what Berkshire Hathaway has as a cash balance. That’s the total capital of the FDIC versus the 9.3 trillion that they have “insured.” It’s a joke.

Kevin: Isn’t that phenomenal? Okay, you were in Disney World recently with your family, and probably Universal Studios, we haven’t talked, but if you go to California or Florida or anywhere where you’ve got these studios, it’s like a Potemkin Village. You’ve got these facades that look like buildings as long as you’re facing the building. But if you walk around the backside, it’s just made out of two-by-fours and Styrofoam. So, what you’re talking about, a hundred and— what’d you say? 128 billion at the FDIC to ensure— what’d you say? $9 trillion? That’s a Potemkin Village. That’s a Warner Brothers Studio or a Universal Studio. It’s two by fours and Styrofoam.

David: Now, this is what I mean. It’s a confidence game. It works as long as confidence can be maintained. The insured depositor isn’t concerned because they’re insured. But what does that mean? It means that if you’re the first bank that goes under, you’re the lucky bank. If you’re anyone after the first bank, you’re in trouble because the money’s already been spent.

Think about this. We already had two banks—it’s actually three—that went under, and it’s taking 700 billion in liquidity from the Fed and the Treasury to solve that problem, which is only multiples of what the FDIC has available to fill holes in those bank balance sheets as they create the shotgun wedding scenarios that we’ve been seeing. So, I think we’re all well beyond assuming that a few regional banks in the US are the only problematic entities within the financial system following the closure of Silicon Valley Bank and the closure of Signature and the closure of Silvergate Capital.

We had that shotgun wedding last week between UBS and Credit Suisse. And UBS picks up its primary Swiss competitor at $3 billion—at a sticker price, at least according to one analyst, equal to the value of Credit Suisse’s headquarter building. They got the whole entity, lock, stock, and barrel, and it all happened very fast. Sequence of events: You’ve got March 15th, the Swiss government saying, “I think we’ve got issues with Credit Suisse,” and they extend them a $54 billion lifeline. So, $54 billion to Credit Suisse should help fill the hole. Stock price jumps 19%, but they still need to go raise some new capital. The bank can’t do it. The bank then faces deposit flight. And quickly you go from a tough story to a terminal case. The credit default swaps—the bank CDS—spike from 300 to 3000, and in a unique twist of fate, one set of bondholders is wiped out. And a few equity holders actually do get paid a couple of billion dollars in the transaction, which is not supposed to happen. Credit is supposed to get paid. Equity is supposed to get wiped out. In this case, credit got wiped out and equity got paid something, even though it was a pittance. Now, there’s always more to the story than reported. Why that had to be structured that way, why the government had to come up with those terms— I’d love to have been a fly on the wall in any of three offices in downtown Zurich or Geneva or Basel.

Kevin: Well, and if you were a fly on the wall, you’d probably also see that US dollars play a big role. I don’t know that the US citizen really understands how we also come up with liquidity for these European crises. Ten years ago that was happening all the time, and that was happening last week as well.

David: Again, we go back to 2008. This is really nothing like 2008, but there’s certainly a few echoes or similarities, and we were willing to say, “Look, we’ve got a subprime problem here. And yes, it’s pretty well contained. We know where the bodies are buried, and so let’s just deal with it.” And the next thing you know, there’s some problems cropping up in other parts of the world. And then, next thing you know, you’ve got companies that are just simply disappearing on other shores all over the world.

This is where there’s an indication of further stress in the global financial markets right here, right now, fast forward to 2023. Global financial markets in recent days—and again, this is just a further indication of stress in the global financial system. This is not just a US-based regional bank problem. Foreign central banks took advantage of the Federal Reserve Foreign and International Monetary Authorities Repo Facility, $60 billion during the week. That set a new record. This is foreign central banks asking for US dollar liquidity, and bringing their Treasurys and using them as collateral for a repo, a loan, with the US Federal Reserve.

This repo facility was set up during the pandemic, but last week saw record requests for dollar liquidity. Is this only about Credit Suisse? Maybe it’s only about Credit Suisse, but this is how things began unfolding in 2008. Ah, we’ve got this minor problem. It’s just a US mortgage issue. In fact, it’s a little carve-out within the US mortgage market. The US mortgage market is huge. This is just the subprime area. It’s so small, you can ignore it.

And all of a sudden it starts popping up because, as it turns out, the global financial system is interconnected. And in this particular case, it’s not so much garbage credit that’s been seeded in portfolios all over the world, it’s actually high-quality credit seeded in every portfolio in every part of the world at zero interest rates. And as we talked about two weeks ago, it’s highly consequential when interest rates rise and the value of those securities drop as a consequence. Very consequential. So, Credit Suisse and then Deutsche Bank come under pressure. Fascinating.

Kevin: Have we not become conditioned to get nervous anytime somebody gets on TV and tells us that something is safe and profitable? Safe and profitable. Deutsche Bank, that’s a great example.

David: Yeah, I was surprised to see—

Kevin: What was the German guy who got on? Yeah.

David: Olaf Scholz. You’ve got the German chancellor, Olaf Scholz, who’s— Financial Times headline, this is four or five days ago, emphatically stating that Deutsche Bank is profitable. It’s safe. Nothing to worry about. That the comment was necessary says something to me. But Deutsche Bank is like every other major global financial firm. It’s highly leveraged. It’s up to its eyeballs in derivative alligators. Credit default swaps, again, default insurance doubles for Deutsche Bank in two weeks. Doubles in two weeks. Derivatives under normal circumstances are used in the normal course of business within finance and banking to hedge risk, and sometimes enhance returns. They can be used as speculative vehicles. But under abnormal circumstances— Like any market, derivatives trade differently under abnormal circumstances. And marginal differences on tens of trillions of dollars in notional value, that becomes meaningful.

This is where you look and say, “Okay, well, Deutsche Bank’s got $620 billion in deposits.” And they’ve got, well, not an insignificant derivative exposure: 42.5 trillion-euro OTC derivatives book. Roughly 30 trillion is centrally cleared, which means it carries little to no counterparty risk. So, you’ve got about 13 trillion that does have counterparty risk—and 13 trillion, again, this is Germany, Switzerland. We’re talking numbers that dwarf the GDP of the country. These are very big numbers. These are very big numbers. Thirteen trillion is significant when your counterparties worry, and you worry about your counterparties.

And again, what did we see over the last two weeks? Gold takes on safe-haven appeal, and there’s a global appetite for it, not just because you’ve got a couple of regional banks and depositors concerned about those banks, but because people understand we have a very complex system and it works very well most of the time. But if some grit gets in the gears, all of a sudden it doesn’t work so well. And it’s too complex to allow for even a little bit of grit.

And I remember 16 years ago, Lehman on a Tuesday— Lehman, they had a solid liquidity position. Their CEO takes the stand, he’s doing interviews and says, “We’ve got ample liquidity. Not to worry.” By Friday, they were toast. And that’s the nature of liquidity in the financial markets. Liquidity can evaporate instantly. We witnessed it on a smaller scale in recent weeks with First Republic. In one week— 70 billion in deposits gone in one week. You’re talking about decades of building a company. In a day, or in a matter of three to five days, 70 billion in deposits walk.

Kevin: Well, and you brought up the FDIC and how little they have. They’ve got the same amount of money, liquidity, that Warren Buffet has. It really is a façade. It’s a confidence game. When I was talking before about the Potemkin Village, it really is just face fronts with two-by-fours and Styrofoam. What would it take though to actually turn those buildings into something real? I think it would take a gold standard, like you talked about Lehrman said.

David: Let’s go back to the end game. Crisis of confidence might open that door to rethink our money. And I like Lehrman’s idea. I like the fact that that could be a consideration. Maybe the ball bounces that way. Maybe we do take the path back to the gold standard. And yes, I do think that the case becomes clearer to a larger audience of people that you need gold as the crisis grinds forward.

But that doesn’t mean that decision-makers—it doesn’t mean that the Ph.D. bureaucrats, that they’re going to vote for it. The modern playbook, like we said earlier, this is one of crisis opening the door to opportunism. And I hope I’m not being too cynical here because I would love to see the ball bounce the right direction instead of the wrong direction. But what we’ve seen over the last decade is, crisis opens the door to opportunism. There is no honest reflection. No politician takes ownership of their policy mistakes. So, the solutions that are offered are ways that you can, in this case, control bank risk, control depositor flight, and control investor behavior. And all of those things are best accomplished both here in the US and universally, using a central bank digital currency.

Kevin: So, a gold standard would actually be the very opposite of the people who are trying to employ this ultimate solution which would bring social control. A gold standard would be the exact opposite of what they would like to employ.

David: Ms. Shedlock posted a request for comment from Federal Reserve. This is docket number 1670 if you want to search it online. So, Federal Reserve request for comment, exploring speedier interbank settlement and improved credit flows. And so, there’s a discussion in this paper of the FedNow Service, describes how it can best be served if it’s built through a quantum blockchain crypto framework. I don’t know how that’s done because I don’t think we have quantum computing quite where it would need to be. But anyway, this is how the paper reads.

The response paper highlights the classic three characteristics of money. You’ve got the unit of account, you’ve got the store of value, you’ve got the medium of exchange, but then they add a rather dystopian—and in my view, it’s a pretty predictable—twist to money as it’s conceived, as it’s contrived, in a future digital form. The fourth aspect of money in the paper is talked about as the means of social control. Money is now a means of social control—ah, but it’s for the good of mankind. It’s for the good of mankind. We’re going to solve the problems of financial inclusion. We’re going to solve the problems of income inequality. We’re going to solve the economic system stability. All of these things are better facilitated by a cryptocurrency compliments of the central banks of the world. So, call it Fedcoin, call it something else if you choose. But the death of the dollar in this round of financial crisis is the rebirth, a fresh look at currency. And with it, a fresh look at social control. I don’t know how we got here. I guess I do, but it’s still mind-boggling to me.

Kevin: Well, and you remember the story that I started with, Dave, the thing that I heard your dad talking about over and over, “We’ll sell you the rope in which you’ll hang yourself.”

David: This is the final stage of a Keynesian nightmare. It really is only a problem for those that remain under-allocated to private, portable, hard currency—gold and silver. We’ve made the case that gold is a means to agency, that gold is an enabler of personal choice. When the language of social control is attached to crypto fiat central bank digital currency, it becomes clear where you ought to be.

Kevin: You’ve been listening to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany. You can find us at mcalvany.com, M-C-A-L-V-A-N-Y.com, and you can call us at (800) 525-9556.

This has been the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. The views expressed should not be considered to be a solicitation or recommendation for your investment portfolio. You should consult a professional financial advisor to assess your suitability for risk and investment. Join us again next week for a new edition of the McAlvany Weekly Commentary.