Podcast: Play in new window

- Why Risk Stocks When Treasury Bills Are Paying So Much?

- Read The Latest Hard Asset Insights – Click Here

American Stocks Most Expensive In Years

August 16, 2023

So if you want to make a case for a strong US economy, that’s fine, but that does not necessarily mean that earnings are going to be continually improving with US companies because guess where they derive a lot of their growth? Someplace else. This is what it means to live in an interconnected world. If China’s hitting a hard patch, if the eurozone is in contraction, I think you actually make a case for being at a critical inflection point. If you’re invested, it’d better not be according to a roll of the dice. It’d better not be according to the classic 60/40 split between stocks and bonds. The battle for investment survival occasionally includes reducing exposures. —David McAlvany

Kevin: Welcome to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany.

I remember when I was 14, Dave, there was a movie that came out called The Powers of Ten. I don’t know if you remember seeing that. It was a short film, but basically what it does is it shows what an ant’s view would be and then what a bird’s eye view would be, and then what a satellite’s view would be. It starts at 10 to the zero meters, and it’s a couple laying on a blanket in a park having a picnic, and then it’s 10 to the one meters and then 10 to the two, 10 to the three, and you start moving out away from the earth, and then you start moving out through the solar system. And then of course it gets to, I think, 10 to the 22 meters. And then it comes back, and it does it again until you get right back down to the park. And then it keeps going until you get down to, I think, a Planck length, which is the smallest that you can see.

But it’s an amazing thing. I’ve got the book at home, too, with each picture in a book, and sometimes I just pull it off the shelf to change my perspective because it’s so important, Dave. We have a tendency to look at things from a certain distance, whether it’s the markets, whether it’s our lives, whether it’s spirituality, and a lot of times we have to change our perspective.

David: Whether it’s relationships or your profession, you need to constantly be taking the 30,000-foot view, and then coming in with a microscope, and then coming back to the 30,000-foot view. It’s easy to get lost in the mundane and the details. It’s also helpful to gain perspective on just how important those details in the mundane are.

So when we look at the markets, I’d say opportunities abound. We study market history to appreciate the degree to which opportunities are fully priced or are trading at compelling discounts or somewhere in between. If the conversation tends towards one extreme or the other, the expression is always one of interest in figuring out how to best steward our resources. And so being mindful of the context that we’re making those decisions within, that’s why we need to come back and forth between what’s up close. And then again, gaining the 30,000-foot perspective. We move to the 30,000-foot view and we try to glimpse where, where on the unfolding timeline we are, and the probabilities of what might happen next. And so that big picture view, moving from the Hubble camera to the microscope and focus on the details for portfolio construction that might be looking at the details of an organization within a particular sector, and weighing its merits as an asset within an asset class. Who’s the team? What’s the process and the progress being made on the promises to deliver value by a particular company within a sphere?

Kevin: Well, and sometimes you just have to get out of the environment completely. I remember a friend of your father’s, actually, and yours as you grew up, was R.E. McMaster. And when he did not feel like it was a good day to trade, if he wasn’t seeing it right, he’d just go out and tend his llamas. Remember, he had his llamas?

David: Right. Well, last week I referenced Ed Easterling, and to some degree he’s removed from the daily grind of the financial markets, chasing cows on his ranch, and he still maintains an aerial view of the financial landscape, but notes like a hawk the small and meaningful movements on the ground. He’s out, he’s got a little bit of perspective, but he still notices the important details.

Being removed has its benefits. And I’ll be honest, there’s some days that I envy him. Less meaningless noise. Maybe a little bit more time to think. The ancients had a phrase, they called it the peripatetic life, where you were the philosopher type if you just walked everywhere and you thought as you walked. And today we want to get from point A to point B as quickly as possible. We remove any possibility of empty space—that empty space being so beneficial to processing information, thinking through, considering implications, and entering more deeply into understanding a particular thing. So less meaningless noise, more time to think. And in that sense, sometimes less is more. The distance from the noise—generated from, I think of them as Wall Street hucksters in their quasi-affiliated news networks—always brings greater clarity of judgment and effective decision-making, or it certainly could.

Kevin: Well, I think also of a guest that we had in the past, Jim Rogers, remember he just got on a motorcycle, he traveled the world to see what was missing in his investment thesis.

David: If there’s one book that I recommend to anyone in their twenties, early thirties, trying to figure out what they want to do with their lives, maybe having some interest in the world of investment and finance, I recommend Jim Rogers’s book The Investment Biker because it brings to life in narrative form the kinds of questions that economists ask, or historically have asked before the mathematization of economics. So yeah, I think The Investment Biker is an intriguing read and one that inspires a curiosity in investing and economic thinking.

Kevin: And another guest that we’ve had is Andrew Smithers. You talked about Easterling, Smithers has been a guest. But years ago, he said, “You know what? The stock market’s getting a little bit too expensive based on my tools.”

David: I read him for years in the Financial Times and then came across a book that he wrote in the year 2000, Valuing Wall Street, simply brilliant. And then I was able to take a class with him in Edinburgh.

Kevin: I remember that.

David: That’s, believe it or not, it’s approaching 10 years ago.

Kevin: Wow. Wow. That was the interview with the harp in the background.

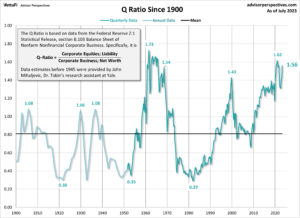

David: That’s right. That’s right. So his emphasis is on CAPE, cyclically adjusted price-earnings and Tobin’s Q, neither of which are market timing tools, but a way of gaining perspective on value. And those two insights and his Valuing Wall Street were absolutely critical in my education.

Kevin: In an airport, it’s good to know the older pilots. I remember when I got my license, sometimes you don’t know whether a crosswind is just a little bit too much. And sometimes you look at the clouds and you may not understand what you’re seeing. But old pilots, a lot of times they’ll know when to fly and they’ll know when to stay on the ground. And a lot of it is just based on past experience.

David: My nephew is at the other end of that spectrum, a younger pilot, sent us pictures over the last few days. I didn’t realize that he had traveled overseas. But he’s gotten his pilot’s license and he’s helping ferry a plane back to the US. So here are these pictures, and I’m fairly certain it’s the pyramids in Egypt.

Kevin: Really? Well, that’s an exciting point.

David: And I’m looking at this, and the next picture in the series is over Venice, and then Greenland. Anyways, I digress.

But going back to Easterling and Andrew Smithers, either of these gentlemen could have penned the article in the most recent edition of the Economist, the piece titled, “American Stocks are at Their Most Expensive in Decades. Are They Worth the Cost?” They’re looking at a different measure, equity risk premium. And on that measure too, you could conclude that this is the time to be cautious while others are greedy. Buffett filled out the other side of that equation a few years back when he encouraged you to be greedy when others are cautious.

Kevin: There is a question out there right now, and that is, do you want to take a risk and get an average of what, 4% or 5% in the stock market, or do you not want to take a risk and get about 4% or 5% in the Treasury market?

David: Yeah, it goes without saying that stocks, in a number of respects, are riskier than bonds, but one is a bet on company earnings and the upside that you’ve got to growth within an industry or with a company that’s executing well. The other’s a guarantee of payment. You get interest on a principal balance that’s been loaned out. And so the gap between the two, factoring in earnings, Treasury yields, share price, that’s what’s known as equity risk premium. And it shows how much of performance gap is priced into the two.

Kevin: And there isn’t one now, is there? I mean, is there really an equity gap?

David: That’s what the Economist article points out. The equity returns maintained over the last 30, 40, 50 years, that premium has averaged 4.7%. That’s over bonds. Earnings yields for the S&P 500 now very similar to that of Treasury yields, the 10-year, without a premium for increased risk. So it’s reasonable to ask: Why, now, would you be interested in taking more risk without more compensation for that risk? So the conclusion is very much in line with what you’d surmise if you were looking at Tobin’s Q.

Kevin: Which was Smithers.

David: Yeah, originally Tobin himself, but certainly Smithers pointed to this measure where you’re looking at the value of equities, their replacement value, and you can get these numbers from the Fed’s Z.1 report where it gives you an aggregate value of corporate stuff, so to say. And if the stock market is selling at a premium above the stuff, then it’s expensive, and it can be on a range from mildly expensive to insanely expensive, and it can also sell at a discount to its replacement value as well.

So Smithers says the simplest rule is to hold stocks when Q is below average, and to hold cash when it’s above. Smithers qualifies that very simple rule by saying that it’s not when stocks are expensive, but when they are very expensive that it makes sense to hold cash.

Kevin: Which is not a huge percentage of the time.

David: No, roughly 17% of the time. If you’re looking at 100 years, 17 years out of that a 100-year stretch, timeframes in which you should be prioritizing cash and maybe considering how extended you want to be into the equity markets.

Kevin: So are we very expensive right now on Tobin’s Q?

David: He defines very expensive as anything above a 50% premium. That qualifies as very expensive. That is, by the Q ratio. We reached 61% in the second quarter of 2021. You recall, we’ve talked about the everything bubble. Well, stocks were right there amongst the everything bubble. So it’s trended lower since then. The most recent calculation based on the Fed Z.1 report is a 56% premium.

Kevin: So very expensive.

David: Yeah. And a reading of undervaluation is marked not just by giving up the premium over its replacement cost, but quite frequently when the trend going from overvaluation lower, when that trend gets in place, it continues for some time and takes you to some pretty intriguing discounts. So from premium to discount, it doesn’t stop at fair value.

Kevin: Yeah. So will we see that, or when will we see that?

David: Smithers would, I think like the Economist article I referenced, fully admit that whether it’s the Q ratio or equity risk premium or cyclically adjusted price-earnings, he would fully admit that these measures are inadequate trading tools. What they do is they provide insight into future returns and the farther out you move on the time horizon, the increased probability, the increased accuracy of the results. So in the next year, maybe we don’t know what happens. In the next two years, we’ve got a pretty good idea of what happens. Over the next three to five years, we know really what is going to happen. Over the next seven to 10, we know more or less precisely how it’s going to happen.

Kevin: Well, and I brought up a movie from 1977, but we are back in the ’70s with the inflation. So I’m wondering, does inflation affect these tools?

David: Yeah, if we go back to the extra return you can usually expect from investing in equities versus bonds, that extra compensation for extra risk taken, it’s gone. So you now are taking extra risk without extra reward being likely. And that setup is not ideal for the long-term investor in equities. So for case for cash is a strong one. You could even argue the case for bonds over stocks is a strong one. But—and this is a big caveat—there, I would proceed with caution. Even after last year’s bond market bloodbath, the new cycle dynamics that have inflation in the equation in ways that have not been seen for many decades, that portends a challenge to that asset class as well. And I’ve read some really strong arguments for being in bonds today. And I’d say, well, maybe, but short-term bonds in my view would be the exception. That is a place where you could be, and be safe. You don’t want to take a lot of duration risk given the fact that inflation is anything but tamed at this point. So the risk of downside in longer-term bonds remains very high.

Kevin: And Dave, of course, you’ve had an interesting background through your life because you were raised in this environment around your dad, but you went into the Wall Street realm. And of course the Wall Street training is that if you’re worried about stocks, you go into bonds. If you’re worried about bonds, you go into stocks, but you certainly don’t go anywhere else. That’s that 60/40 portfolio. But there is a problem because that didn’t work a couple of years ago.

David: And the general setup is this, you talk to a financial advisor, he asks your age, you subtract the age from 100, and that gives you the rough split between how much you should have invested in equities versus fixed income. And so roughly speaking, what we witnessed is this sort of averaging out of ages and demographics, 60/40 portfolio. And that’s 60—

Kevin: 60% stocks, 40% bonds, right?

David: Yeah. Or, if you’re moving towards retirement, you’d fluff that around.

Kevin: Flip it. Okay. Right.

David: Exactly. So in 2022, you had contemporaneous losses in both assets, and that leaves the seasoned investor of yesterday in a real quandary, what does safe haven investing look like in this period of market history?

Kevin: But the question would be, are we going into a recession? Because if you look at the news, we’re not.

David: Well back to the Wall Street hucksters. You get a view, a strong view from the people who are selling stocks and bonds that there’s never been a better time to be buying stocks and bonds, says the salesman of stocks and bonds. And of course you’ve got the unaffiliated news networks which support that. They’ve all but dismissed the possibility of recession. And this is largely based on, if you just count the votes, counting PhD economist votes on how this year ends and 2024 begins. So the consensus has gone well past recession, gone well past a soft landing. Consensus is now somewhere between Nirvana and Goldilocks, sort of a middle ground. Even that soft landing recession is being downplayed.

Kevin: But these PhD economists, okay, these guys that are always telling us whether we’re going to have a recession or not, does anybody track the results?

David: Well, it’s interesting because the one thing they seem to lack—I don’t doubt the pumping of the dendrites and the general intelligence and how fast their C fibers do fire—but I think they don’t have very good memories. A must read is the brief nostalgic write-up in Hard Asset Insights this past weekend—second week in a row of just knocking the cover off the ball—Morgan, my colleague. We’ll include the link for that.

Kevin: Yeah, that’s at McAlvany.com.

David: Whether it was recessions in the ’70s, the ’80s, the ’90s, or 2000s, economists have consistently downplayed recessionary outcomes and prepared their curious readers—the ones who are engaged—prepared them for a soft landing as a worst case. And they’ve done that over and over and over again. Hard Asset Insights covers the batting averages for those professional prognosticators, and, turns out, they’re extraordinary. Extraordinarily poor.

Kevin: Yeah, right.

David: They’re not batting 1.000, clearly. Not .500. Not even close to sort of the Ty Cobb, Joe Jackson, Babe Ruth averages of .342 to .366. And my cursory research shows that Chris Davis—this is a tough position to hold—but Chris Davis coming in at 0.168 was the worst batting average in Major League Baseball history. You know what? He looks great compared to the PhDs who struck out on every major swing at the bat. When it comes to predicting recessions— What’s fascinating is they do predict eight out of the four recessions that we have, and they seem to gloss over the ones that actually show up. So there’s something about the mindset. And then, in addition to the mindset that doesn’t allow them to see it, they can’t remember when it happens to them either.

Kevin: That quote, it’s funny that you just had that eight out of the last four because I just had a listener who’s a regular listener quote me the same thing. He says that’s his batting average as well. And it is good to have some humility there. But so let’s say that we don’t have a recession or we do, these tools that you’re talking about, whether it’s the Q or the cyclically adjusted price-earnings ratio, they’re all pointing to the fact that the stock market is expensive right now.

David: Yeah, I mean the backdrop in the major equity indices is one of overvaluation. I looked at a handful of stocks and a few things that we’re interested in as a company, reasonable P/Es, very intriguing earnings profiles. But again, generally speaking, if you’re looking at the cyclically adjusted price earnings ratio, that’s a 10-year rolling average of P/Es. Looking at Tobin’s Q, the replacement value of stocks compared to current pricing. Price to sales. And we brought in the Economist article from the most recent issue, equity risk premium. The attitude towards the US economy is sanguine, superior by far compared to the rest of the global economy. Look at what the US economy is churning out, and yes, we’re doing quite well versus China, quite well versus the eurozone. Germany, it’s flat sick. And then you’ve got the possibility of a speed bump, the probability of a pothole, the potential for a cave-in here in the US economy, economists would say absolutely not. No speed bump, no pothole, no cave-in, completely roundly dismissive.

Kevin: Do you think it’s the mixed messages though? Because we’ve got interest rates on the rise right now, and if we were going into a recession, wouldn’t we start to see a fall in interest rates? Wouldn’t that be something that the Fed would try to get in front of?

David: I think some of this has to do with meaning, and I’m reminded of the importance of grammar, even commas, as something that can save lives. You’ve probably heard this joke, but commas save lives. We’re having grandma for dinner. We’re having grandma, for dinner. Details matter, and the meaning implicit to what people read is not always clear. So in some cases you’ve got economists looking at the statistics in front of them saying, yep, this is a recovery. Why is the 10-year Treasury flirting with a breakout? Four percent is a line of demarcation, and a traditional recession would suggest a move lower in interest rates. We deal with how people understand these things. What do they mean? Is that true that as interest rates have gone higher, that it’s an indication of economic strength? Or perhaps it’s an indication that inflation has yet to be killed? It’s not dead yet.

So a traditional recession would suggest a move lower in interest rates, yet rates in recent weeks have been flirting with the highs of last year, and they’re attempting a breakout to higher levels. So again, what does that mean? Where does the comma go? How do we read this particular data?

Kevin: So the virtuoso of interest rates right now, Bill Gross, he was Mr. Interest Rate for decades, he thinks it’s going higher.

David: And again, this is where one economist reads that as an indicator of improved economic activity. The bond markets may be voting that inflation is not yet dead. I’ll never forget the Monty Python, the guy who’s thrown over his shoulder, “I’m not dead yet.”

Kevin: “Yes, but you’re not coming back till Thursday. Go ahead, take him.” “I’m not dead yet.”

David: Well, Bill Gross sees a clear path to 4.5% on the 10-year. Why does that matter? Perhaps he’s the past bond king who has ceded the throne. Maybe he does see something. We close the second quarter the end of June with the US long bond year-to-date gain of 5%. Since then we’ve flipped to a year-to-date loss of 2%. This is just since June 30th. So a seven percentage swing, what was a gain is now a loss. The 10-year, a slightly shorter duration, has stretched past 4% early this week to 4.2%.

Kevin: And Gross is saying we’re going to see 4.5%.

David: Yeah. If rates continue to move higher, something else will break. That’s why it’s consequential because the system of debt that we’ve built can’t afford higher rates. And this isn’t just the Silicon Valley Bank episode of 2023. This is Black Monday, this is the tequila crisis, this is the dotcom bubble’s encounter with a pen. This is the global financial crisis.

Kevin: All of those had something to do with interest rates.

David: Well, think about Powell. Powell’s pivot in 2019, he’s finally getting tough. He’s not just talking tough, but then he has to reverse course very quickly. Why? Interest rates are beginning to break things down. All of those instances were accompanied by rates increasing to a critical level and precipitating a major market disruption. While it may not seem like a big deal for rates to have moved from 3.75% in July just a few weeks ago to 4.2% in August, this is an uncomfortable territory for any debt instrument that takes its cues from the 10-year.

So now you’re talking about, by extension, vulnerabilities in the mortgage-backed securities market. Why does that matter? Well, look, if the mortgage-backed securities market begins to come unhinged, you’re talking about the finance mechanisms for housing. We know that a near 7% 30-year fixed rate mortgage is artificially low because Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac are there to subsidize the cost of long-term borrowing. But if there’s trouble in the mortgage-backed securities market, maybe we don’t see Fannie and Freddie able to hold rates at an artificially low number and it gets repriced to higher levels. You tell me what happens to real estate if you’ve got an 8%, 9%, 10% 30-year fixed rate mortgage. There’s plenty in our audience who were there, finance their homes at those or higher numbers, and they know that on the other side of that seesaw is the price of their home. Higher rates equals lower home values.

Kevin: So it reminds me of spring ice. Okay, when you’re walking across the lake in the spring, you’re right on the border of stable and unstable. You’re either going to stay on top of the ice or not.

David: Yeah, you’re probably good.

Kevin: Mostly. Mostly good.

David: You’re mostly dry. Yeah. To go back to last week’s comment, if commodity prices and base rate effects keep the inflationary pressure higher, rates may well break out to the upside. And then there is the unfolding drama in China, which have nothing to do with interest rates, but again, we look at the volatility in the financial markets which can be queued off of one number and then go across the pond to drama which can be queued by one decision. And you’ve got the potential here to create a safe haven bid in Treasurys with a steep decline in a short period of time. So here’s this catch-22 of, you can make the case for higher rates. You can also make the case for significant geopolitical crisis leading to a rupture in the financial markets and, on a very different basis, people scrambling for US dollars and rates coming lower. It’s not easy.

Kevin: Well, not only is it not easy, but you brought up China. China could just be a whimper right now. Yeah, it reminds me, speaking of a whimper, you try to figure all this out in a quiet environment. You were talking about that earlier. Pretend like you’re in a quiet theater, you’re watching a quiet movie, and the first 10 minutes of Saving Private Ryan is next door. And that has happened to me, all right, where you’re sitting and listening in the movie and it’s like, oh my gosh, there’s a war next door. That could happen with China. We can talk all we want about inflation and being on the cutting edge of interest rates going up or down, stocks being overvalued, all of that’s the environment of the quiet theater still. But right next door, we could have Saving Private Ryan go off. I mean, this Chinese thing is a big deal if they don’t get control of it.

David: Kevin, my disappointment for the day was reading through an essay, “A Requisite for the Success of Popular Diplomacy.” I’m reading through it, I’m going, this guy, he’s articulating things in such a clear way and it’s so relevant to what we need right now. And I’m like, we should have him on as a Commentary guest. I’m thinking, he speaks with the authority of a kingmaker. He speaks with the authority of a chief advisor, and it’s just very clear thinking. It turns out he died in 1937.

Kevin: Darn.

David: He was Secretary of War—

Kevin: Our best guests have been dead for decades.

David: Secretary of War in the cabinet of President McKinley and Secretary of State under President Roosevelt. So I only found that out later because I thought, oh, I’ve got to see what else he’s written, and I didn’t realize—I probably should have realized that with a name like Elihu, he wasn’t born yesterday.

Kevin: Yeah, yeah. Well, Jacques Rueff was like that as well. He had been gone decades before we discovered him, and we thought, gosh, this guy would be a great guest. But no, he was gone.

David: This week, one question that our team lingered on was, why, with the unfolding drama in the Chinese markets, has there been no safe haven bid in US Treasurys? And I’ll tell you, between the end of last week through the weekend and how this week has started, you’re talking about just an absolute tender box for the financial markets.

Kevin: And so what you’re saying is normally people would go in and safe haven buy Treasurys, and the percentage that the Treasurys have to pay would drop?

David: That’s right. Based on demand, the price goes up and the yield comes down. In this case, there’s been no safe haven movement, no migration, and no drop in yields. So I don’t know, has the People’s Bank of China convinced the markets that they have the real estate sector unwind quarantined and controlled? I mean, it’s very unclear. Is there an expectation of shock and awe intervention that will save the sector or that will adequately stimulate the economy?

One thing’s for sure. In the last week, Beijing has been scrambling to sort out local government finance vehicles. They’ve abused the land sales and generating lots of funds from that. They’ve accumulated, believe it or not, $13 trillion in debt, and a lot of that is unsound. You can assume it to be bad. $13 trillion in debt, most of it opaque. Again, some of which can assume to be bad. The local government finance vehicles are a large part of the debt problem in China, and maybe that issue transcends the real estate unwind, but that unwind was significantly ratcheted up last week.

Kevin: Country Garden—you brought up Country Garden—in the past, a couple of years ago, had just a normal interest rate. Aren’t they missing payments now? They’re not even paying out.

David: Well, a year or so ago it was Evergrande. Evergrande was the big story in China, and there was a lot of intervention and things seemed to calm down. We’re on the second shoe dropping in the real estate sector within China. And a part of that is because the public has not come back in to buy new properties—and that part of the economy some attribute to 25% of GDP in China is not doing well.

So Country Garden, largest property company in China, has gone from 7.5% yields at the beginning of 2022 to 17% yields, this is on its debt, at the beginning of 2023, to 192% this week after missing payments on Friday. Now, if we were talking about equity prices and it went from 7.5% to 17% to 192%, you’d be pretty happy. But this is not the case. Their equity shares are now penny shares. They’re a penny stock.

Kevin: Wow. Yeah, you want 192% from a company that didn’t pay its bond payment this week?

David: It tells you that no one’s expecting them to pay, which is why their debt’s trading, some of it’s trading at 6, 7 cents on the dollar. A lot of it’s trading in the 10, 11 cents on the dollar range. So another month of disappointments for the Chinese economy. If you’re looking at imports and exports, both were down double-digit and well beneath what was expected, even though they had lowered the bar in terms of expectations. You’ve got global firms which are backing away from Chinese investment, not just investors from the stock market, say the Shanghai or what have you, but investment partners in China who’ve been building infrastructure and things like that. In China, one measure of foreign direct investment is now down by 87% from the same period last year.

This week with fresh pressure in the real estate market, the RMB is under pressure, so the Chinese currency is back under pressure. Capital flight has been on the increase, and what they’ve done to counter that is some very high profile arrests of companies that were helping wealthy people move money outside of the country. So the capital flight is being addressed with arrests and imprisonment. I mean, we are talking about being in a very interesting market juncture.

Kevin: And so it’s hard to make a case for the Chinese economy being strong when you’re imprisoned for wanting to move your money out. How about the US economy? Make a case for me that the US economy is strong.

David: Well, catch this. The prohibition against even saying anything negative about the Chinese economy—you can go to jail for saying anything negative like, oh, we might have deflation. Off you go. It’s absolutely fascinating. It doesn’t matter if you are in the news media. It doesn’t matter if you’re an academic. It doesn’t matter if you’re a man on the street with a sandwich board saying whatever your sandwich board says. No, no, you cannot. You cannot say anything that would suggest there is a reason to doubt the confidence which they’re hoping is maintained in major central planned policy objectives. It’s just not happening.

Kevin: Yeah, so they’re forcing it, but let’s go to the US economy because people are operating as if the economy is strong. You talked about Smithers, and we were talking about the various ratios and the various tools that are saying the markets are overvalued, but it doesn’t seem that anybody cares.

David: Well, I think one of the things we have to reflect on is that what happens in China does not stay in China. What happens in Europe does not stay in Europe. What happens in emerging markets does not stay in the emerging markets. If I were to look at the S&P 500 and say, okay, of these big corporate conglomerates, where are they generating their revenue? We’ve done a really good job of transitioning to a very diverse source of revenue, and you could point to roughly half of the revenues for your Fortune 500 companies coming from overseas.

So if you want to make a case for a strong US economy, that’s fine, but that does not necessarily mean that earnings are going to be continually improving with US companies because guess where they derive a lot of their growth? Someplace else. This is what it means to live in an interconnected world. If China’s hitting a hard patch, if the eurozone is in contraction, I think you actually make a case for being at a critical inflection point. Now, I don’t know if that critical inflection point is Q3, third quarter of this year, we’re in it right now. Later in the year as we get to the fourth quarter. First quarter of 2024. I think, like the Q ratio, the farther onto the horizon, the higher the probability of major financial market disruptions that are in turn reflected in what is presently an overpriced equity market.

Kevin: So when you are standing on the tarmac or on the runway and you see a bunch of old pilots who were going to fly, but they’ve decided not to play that day— I’m just thinking, if you don’t have to play, if you don’t have to be in the markets, why suffer through this uncertainty?

David: Yeah, it’s impossible to predict how these global financial dynamics play out. Part of them are financial, part of them are geopolitical, part of them are economic, which have consequences into every other’s sphere, both political, geopolitical, and financial. But one thing is certain: certainty is a bad idea. If you’re really cocksure about where you think things are happening in the timeframe it’s going to happen, the markets are going to teach you some humility. Current events are very difficult. We don’t understand the resolve.

I was explaining to someone just this last weekend the conversation we had with Otmar Issing when he described his first day at the European Central Bank. And he described a resolve to fix things, and impertinence in the face of factors within the eurozone which no one liked, but were allowed because there was something else at stake. Do you remember him saying—

Kevin: Oh yeah, I remember.

David: —“My father was a prison guard. My compatriot, whom I met and had lunch with the first day there at the ECB in the canteen, his father was a prisoner in that same camp. We looked at each other and we knew that we had to fix things, and it didn’t matter what the cost was. Because somebody asked me, it’s such a fiasco, the European Monetary Unit, so many people hate it.”

Kevin: And he said, it’s better than having a World War III. They never wanted to have that happen again.

David: That’s exactly right. So we don’t know the level of resolve of politicians and policymakers. We don’t even know the motivation. Some of them are very good and some of them are completely malignant. We don’t know how this plays out. We return to Easterling, we return to Smithers and the host of valuation indicators, which suggests that, as you said, Kevin, if you don’t have to play in these markets, you should not play in these markets.

If you’re invested, it’d better not be according to a roll of the dice. It’d better not be according to the classic 60/40 split between stocks and bonds. You might just relive the 2022 double barrel blast as a first round, as a pre-shock for the main event yet to occur. The battle for investment survival occasionally includes reducing exposures. It occasionally includes having a fortified insurance position. In that respect, should you own gold? Absolutely. Smithers points out that it’s only 17% of the time that it makes sense to favor high cash allocations.

Kevin: And this is one of those times.

David: Most of the time it pays to be bullish, but new cycle dynamics suggest that we’ve passed the point of no return, and that surprise is more likely not on the upside, but the downside this time.

* * *

Kevin: You’ve been listening to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany. You can find us McAlvany.com, M-C-A-L-V-A-N-Y .com, and you can call us at (800)525-9556.

This has been the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. The views expressed should not be considered to be a solicitation or a recommendation for your investment portfolio. You should consult a professional financial advisor to assess your suitability for risk and investment. Join us again next week for a new edition of the McAlvany Weekly Commentary.