Podcast: Play in new window

This week’s McAlvany Weekly Commentary covers the shifting global financial landscape through the lens of tariffs, gold’s historic surge, and structural market volatility. David walks through the implications of what may be the end of the Bretton Woods era as we’ve known it, and why investors should be paying close attention to the signals coming from both financial markets and real assets.

We also highlight David’s new white paper, a timely analysis of gold’s breakout to all-time highs and what it may be telegraphing about the future of currency stability, capital flows, and global trade.

Click here to read David’s latest white paper on gold’s record highs, the unraveling of Bretton Woods, and what it means for your portfolio.

Read the full paper →

Two featured charts this week provide deeper context:

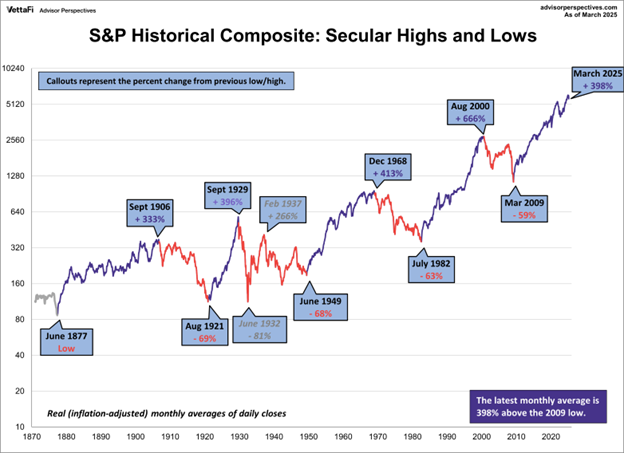

S&P Historical Composite: Secular Highs and Lows

A look at more than 150 years of inflation-adjusted S&P 500 performance. With the index now 398% above its 2009 low, this chart raises important questions about valuation, cycle exhaustion, and what comes next.

Treasury to Gold Ratio – Gold Preferred

This chart tracks the long-term relationship between gold and long-dated U.S. Treasuries. The recent surge illustrates a major shift in capital preference toward hard assets—an essential dynamic to understand in the current environment.

David also discusses market behavior over the past week, including key differences between asset classes, how forced liquidations are impacting prices, and why this environment reminds him of the 2008 deleveraging cycle—only with deeper, more systemic undercurrents.

“Gold has been signaling for a number of years that we are at a very important historical inflection point. Gold surpassed a 25% return last year, rose over 19% in the first quarter of this year, and it’s signaling structural changes are occurring. Smart money has been positioning ahead of that.” —David McAlvany

* * *

Kevin: Welcome to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany.

David, I can’t keep things straight. I’ve been listening to clips from Pelosi and she’s been talking about the need for tariffs, but this goes back to the 1990s. I think Schumer said some things. Obama obviously was very, very vocal. I mean, what gives, are they no longer saying the same things or driving Teslas anymore?

David: Well, clearly the market is shocked by the extent to which tariffs were introduced last week. And of course the response from the Chinese on Friday didn’t help things because it suggests that we’ve got a war on our hands, not just a slap on the wrist from the US administration for a variety of our trade partners.

But you go back through the clips with Chuck Schumer and Joe Biden and Bernie Sanders from 2005 to 2019, they all advocated for massive tariffs, particularly with China, and their current condescension and critique of the president’s policies are, in point of fact, disingenuous lies. They misrepresent what they have strongly advocated for over the decades, a better deal for the middle class and working-class families.

The left objected to many of the concessions given to our trade partners during the recent decades of globalization flourishing, and now Trump is singing from their song sheet, and the left has to object because it’s Trump.

Kevin: And let’s just face it, Dave. I mean, we’ve done this commentary now, what is it? 17 years. The economy and the financial world has just gotten more bloated and more bloated and more bloated. It had to correct at some point. So I don’t know that the tariffs have to be blamed for everything, do they?

David: Well, I think it’s important to draw a strong line of distinction between the economic goals, the economic outcomes of the tariff regime and over-leveraged, overvalued financial market because that bubble is in search of a pin.

The financial bubble was going to burst. Now, you have a source of uncertainty that acts like the pin prick we’ve long anticipated. How far down these markets go is anyone’s guess. But undervaluation—the other extreme of this continuum we’re on, just now starting from overvaluation—undervaluation is the rough destination and it’s still a long way off.

Kevin: Well, now of course you’re talking about the stock market and—Morgan just brought out this morning—probably the bond market. So, not all markets are created equal, though, even if they equally fall on some days.

David: Well, trading across all assets has been volatile in the last week. The largest intraday swings in the S&P 500 in over a decade, according to Bloomberg. There have been differentiated days with very different signatures, and the details absolutely matter here. What is unfolding involves every investor, but not everyone at the same time or in the same way or with the same ultimate result.

Kevin: Don’t you think Wall Street versus, say, the middle class— Wall Street got pretty spoiled to market interventions, but Trump is pulling for the middle class right now?

David: Yeah. Tariffs are posited by the White House as something that’s good for the middle class and the best and last opportunity to shift the system from predominantly consumption to having a more balanced production profile, from being goods takers to returning to being goods makers.

How realistic that is, or how long a transition like that takes, is very difficult to know. But the fallout from this shift has immediately been felt across markets. Starting the month of January, 1st quarter, we leaned heavily on market uncertainty being tied to price volatility. Those are the overarching themes for 2025. That’s what we thought then. We continue to think that now.

The post-Rose Garden tariff fallout brought every asset class and every geography on the planet into this grid. Being more aggressive than anticipated—that is, Trump—financial markets are now discounting a future that may include stagflation—or worse, an outright depression. Or maybe the markets are just correcting off of extremes and it has nothing to do with stagflation or depression.

To date, we are not in or anywhere close to a recession. There’s certainly a change in sentiment, which can be the first indication that that’s where we go next, but we have yet to see the measured move lower in industrial production, in non-farm payrolls, in real inflation-adjusted incomes and real retail sales. If you’re looking for one spot of weakness, it’s only retail sales lower by 3.23% off of their all-time highs as of the February data.

On the payroll side, last week 228,000 jobs added in March versus 137,000 expected. There is, to date, a contrast between financial market sentiment, which is now dark and bearish, and economic functioning, which actually, at least at this moment in time, not so bad.

Kevin: I’ll never forget, my first year with your family business here at McAlvany was in 1987, and your dad wrote in August that the market was over-bloated and it was probably going to crash. Well, sure enough it did. And the strange thing though, Dave—and this comes from forced liquidations—I had just come out of being a toy store manager. That’s what I was doing when I was in college. Toy store stocks and gold stocks took the hit the worst back in 1987, yet gold, even though those gold stocks had fallen almost 30% at the time, it ended up by the end of the year. I think it was an October crash, and it ended up by the end of the year. Same type of thing happened with physical gold in 2008. So these forced liquidations, in some ways, give you an incorrect meter as to what to own.

David: Yeah, time will tell if it’s too dramatic—that reference to recession, stagflation, or even depression. But with leveraged speculators being forced to unwind trades in a short time frame, meeting margin calls, redemption requests for their funds, this looks like a market that has a lot further to go on the downside. So if we just take a snapshot in time, the market is oversold, it will either rebound higher of its own accord or rebound higher on the basis of some Fed or Treasury official sowing promises of stabilization coming from market intervention. So now, we have an unwind of hedges, the short positions which people were putting on to protect themselves from further downside, and that’s likely to drive prices higher.

But don’t be fooled. The journey to undervaluation in equities is long and arduous. And to your point earlier about this stretching beyond equities to other asset classes, Doug, in our Monday meeting this week, said equities at this point are a sideshow. Watch the bond market. And sure enough, bond yields are rising. Typically, when you have a decline in equities, you’ve got a flight to “safety,” and you’ve got buying pressure in fixed income, which pushes prices higher and yields lower. When you begin to see yields go higher in the context of an equity market sell off, it does suggest that the stress is very much systemic and very much worth paying attention to.

Kevin: Well, and Dave, oftentimes people say, “Well, gosh, if I just ride this thing out, it’s not going to be that bad.” But when you’re talking the stock market, didn’t you say in our meeting that the average bull market was, what, 300 to 400 to 500%, but the average downturn was over 60%?

David: I’m going to attach a chart in the show notes.

Kevin: Okay.

David: And it shows the S&P historical composite, and looking at the secular bull market and bear markets. You can see that secular trends average 350 to 400% in gains, if you’re talking about a bull market, and the secular bear markets are followed, typically, by average losses of 68%.

So let me say this again, if this is a secular bear market, if we are currently in a secular bear market, expect a—conservative estimate—50% loss off the peak; 68% is the average loss from previous secular bears. Again, this is 69, 68, 63, 59, 81%. That’s the extent of the bear market sell-offs in previous secular periods. So 50% wouldn’t be a surprise at all. You’re Dow trading from 44,000 to 22,000, not out of the realm of possibility by any means.

Kevin: Well, and this is a good reason to balance it out with cash and gold, the new word that’s been invented to get you to not sell based on this thought of it being a bear market is called a “panican.” Don’t be a panican, is what they’re saying right now in the news. But actually, you don’t want to be an optimist or a pessimist. You just want to be a realist during a period of time like this.

David: Yeah, I think sentiment has shifted, which is one of those things that you’ve got to pay attention to. Positive sentiment continues to drive prices higher, and it’s usually inspired by ample liquidity. If liquidity begins to be constrained and positive sentiment is disappearing, you can expect lower prices. We’re talking about rising bond yields. That is a strong indication that liquidity is being squeezed. And that’ll be like a force multiplier for negative sentiment.

So back to the differences in trading behavior from one day to the next. Markets sold off on Thursday, this is last week. And there was little impact to hard assets, and we’ve seen this in recent weeks as negative pressure has built in financial assets broadly, hard assets have outperformed.

Friday took on a very different character. The selling was broad-based, it was steep, and it was driven by hedge fund forced liquidations and margin calls—what the Financial Times described as the largest concentrated forced liquidations in hedge funds in living memory.

In that context, gold, silver, hard assets more generally caught up on the downside. Monday was a bit of follow-through with no Fed or Treasury assurances provided through the weekend. The selloff continues. We’re now in a trade war, says the market. It’s concluding that this banter—not so friendly—Thursday and Friday between the US and the Chinese trade envoys, things are going to get worse.

And that’s what we see reflected in the pricing. Margin calls, forced liquidation takes on a unique tone. It’s not unlike the October, 2008 period of deleveraging. Gold was a marginal source of liquidity for imploding portfolios. It provided—once you liquidated it—it provided much needed cash. It was sold. That was just prior to repositioning and returning to a strong metals allocation—almost immediately re-bought. Hedge funds owned it. They were forced to sell it, and then bought it back again as a primary assurance against counterparty risk.

Kevin: Right.

David: I think we’re seeing a similar dynamic now. Beyond deleveraging, the metals markets are well-supported by what Mohammed El-Erian described over the weekend as the 3S change in how things work: secular, structural, systemic.

Kevin: Dave, you just recently wrote a white paper on the things influencing gold. I would like to, one, attach that, that’ll be another attachment to the commentary, but let’s go ahead and consider the gold market in the present context through the lens of those elements that you talked about in the white paper.

David: Yeah. So through the lens of currency stability, international relations, domestic policy, capital flows and trade settlement, and of course the behavior of the global financial markets, which we’ve been talking about. These categories are, as Mohamed El-Erian describes, these are structural, these are secular, these are systemic, and they leave us exceedingly bullish on the metals, and frankly bearish otherwise.

Kevin: Well, and so let’s start out with currencies because when I move out of the dollar, I want to move into gold.

David: Yeah. Currency stability, the reason I put gold in the context of currency stability is because it ties to an old law, Gresham’s law. A monetary principle that states bad money drives out good money. This means that when one form of money is viewed as inferior, it is exchanged for the superior form, and the good money then disappears from circulation. Does that make sense?

Kevin: Yeah.

David: So when currency stability concerns emerge, savers seek alternatives which preserve their purchasing power.

Kevin: It reminds me of Argentina, when we went to Argentina, Dave.

David: Yeah. Under the bimetallist system, that might include shifting from silver to gold, the superior form. Under fiat systems—again, these are paper money systems with no tangible backing for that currency system—capital flows to a superior fiat, and, exactly, Argentina. When we were there, savers were keeping safe deposit boxes full of US dollar cash.

Kevin: Right.

David: That is an example of Gresham’s law. If inflation thresholds exceed tolerable levels, capital moves to safety. Only in the present era—and this is sort of since 1971 to ’76. ’71 was when Nixon closed the gold window. ’76 was the actual end of Bretton Woods. Only in the present era have fiat currencies lost a stable reference to value themselves against. So currencies are floating, and we have value in the fiat currency system relative to other constantly shifting currencies.

Kevin: So let’s go back to when gold became the thing that was measuring everything else.

David: Yeah. For thousands of years. I mean you go back to the Lydian Empire, gold has been the enduring reference point. Gold demand in the present period tends to rise in value when devaluation concerns increase, when competitive devaluations between trade partners are a real threat.

You can see how this is taking shape where currency stability has to now be not just a back burner issue, but a front of mind, front burner concern as trade partners are considering what it means to navigate a trade war. Even though gold is no longer a part of our monetary system, it serves as a signal for growing concerns that bad money is proliferating, and it takes on that historical good money role.

Kevin: One of your favorite authors, and you’ve interviewed him numerous times, is Harold James. And he talked about the periods of time when we had globalization, and actually, they were stabilized either with gold or let’s say the petrodollar. But he has been warning now for two decades that international relations through this period of globalization could be ending.

David: Yeah. If you look at gold through the lens of international relations, it is interesting. Peace encourages cooperation, peace enables trade, and long periods of peace stimulate confidence. And if market participants experience this confidence, they’re willing to take risk. You see examples of business adventurism that creates a tremendous amount of wealth, assuming that they’re successful.

So under these conditions, capital flows freely. The cost of capital tends to decline. So there is a peace dividend, right? So looking at the last several hundred years, there’ve been two periods of globalization. The first, 1846 to 1914, which was ending in the late 1920s and ’30s. The second period of globalization began in the 1960s and ’70s and arguably is ending now.

Kevin: Well, and you had communications, too. I mean, going back to the 1800s Morris code and the cable underneath the ocean, that was critical to linking the world and actually increasing globalization.

David: The world was expanding. It was enabled and furthered by technological innovation. During the 19th century, the global economy was integrated, and integrating more all the time. It was a period that reinforced the free flow of people and of ideas and of information and capital. Between 1871 and 1915, you had 36 million people that left Europe. Talk about globalization, talk about migration. These things went hand in hand. We had the first transatlantic cable, which was laid in 1866. We had steam ships and ocean liners which were on the move. Rails were being built everywhere at a feverish pace. Between 1865 and 1916, the rail network just in the US alone expanded from 35,000 miles of track to 254,000 miles of track.

Kevin: That is extraordinary. And we live in a town that still has some of that track back from the 1800s, basically going up to Silverton.

David: So you’ve got cultural integration, you’ve got an increase in economic activity—again, enabled by technological advancement in running in a parallel track with risk taking.

Kevin: Yeah.

David: With cooperation and peace came a reduction in financing costs. Rates come down, and aggressive investment is made into the future. As the price of time comes down, people squeeze more of the future into the present. Gold in the first period of globalization was a lubricant for trust and trade, encouraging cooperation. And of course the largest gold reserves were in London. London was the banker to the world. Again, this is sort of the period of globalization 1.0.

Kevin: And then came 1914. Okay, World War I.

David: World War I is the first shock to globalization. By the late 1920s you’ve got nationalism, you’ve got protectionism, you’ve got deglobalization, which are all emerging themes. You’ve got Senators Hawley and Smoot promoting a bill that in its final version had 21,000 tariffs attached to it. The world found itself in depression with a collapse in free trade and an extreme restriction to the free flows of capital. Devaluation became a go-to monetary reaction, a default monetary reaction to cover the costs of war and the rising costs of social safety nets.

Kevin: Okay, but we had gold for globalization 1.0, but we didn’t have gold for the second one. We had a petrodollar instead. It was more oil-based.

David: Well, gold was not the lubricant for globalization 2.0 machinery. There wasn’t enough of it to meet the needs of a rapidly growing demography. So what took its place was credit. Credit became king, and particularly so as rates declined. I think the most recent period of globalization and the growth in credit you can see moving ahead as rates declined for four decades, 1982 to 2022, and then, sandwiched halfway into that period, the WTO and the invitation to China to become a part of the global economy after being dormant for as long as they had been. The past is somewhat prologue. We’ve got the unwind of globalization 1.0, which was certainly attributable to global conflict.

Kevin: World War I. Yeah.

David: But the penchant for guarding domestic economic interests, it was alive then. And guarding domestic economic interests, it’s very much alive now. As we transition away from globalization 2.0, the uncertainties stirred by diminished free trade and an increase in tariffs, it’s driving demand for liquid and safe allocations in gold.

You can see this predominantly with high net worth individuals, with institutions, with central banks. But one can argue that during periods of expansion, again, if you could just go back to the first period of globalization and the second period of globalization, ’82 to 2022— You can argue that during periods of extreme growth and expansion, gold is, I don’t know, almost like dead weight. These periods. It’s like gold carries a high cost, opportunity cost. We could be owning something else. We could be doing something else. Look at the growth here and there and everywhere.

However, during periods of geopolitical strain and trade war stress, gold comes into focus as a valuable reserve asset. Again, you see this with high net worth individuals, institutions. We’ve talked about the insurance sector in China. We’ve talked of central banks ad nauseam. They see it as a reserve asset.

So the threat of competitive currency devaluations amongst trade partners seeking an export advantage motivates allocating to gold as a superior reserve asset, stable currency alternative. That dynamic is very much in play today. And again, this ties back to a decrease in cooperation through the end of globalization 2.0.

Kevin: Well, and the real country that suffered from the end of globalization was Germany after World War I. Because if you recall, their currency completely failed. Gold was the thing to have during that unwinding of globalization for them. I mean, granted, it was the end of a war, but let’s go to Trump now. Because Trump Domestic policy— Trump is basically saying, “Look guys, what we’ve done is we’ve sold all our production to all of our enemies, and it’s time to bring it back.” So domestic policy, Trump, the middle class, tie that into gold.

David: Again, it’s important to me that folks understand what’s going on in the gold market and why short-term movements in the market are less important than what El-Erian describes as structural, secular, and systemic in nature. Because I think when you understand what is changing and the scope and the importance of what is changing, you can see that this is in fact a trend, a structural, secular, and systemic trend which does not go away in a day. These are issues which we will have to be dealing with for years, maybe even decades to come.

Kevin: This is a paradigm shift.

David: So domestic policy, we’ve got the Trump administration prioritizing domestic policies at the expense of international trade cooperation. That trend is a part of the adoption of democratic political structure. And it’s not just the Trump administration. If you want to backdate it, this is a notable trend throughout the 20th century.

Kevin: So it’s the voters. It’s the voters at this point.

David: Yeah, and it’s something that you see occur pretty regularly everywhere in the world where democracy is flourishing. Those who are being voted into power have to be sensitive to the people who are voting them into power. So this is a natural thing. You prioritize domestic policies at the expense of international trade, and that is just a part of democracy.

With the rise of suffrage—and this comes from Giulio Gallarotti—with the rise of suffrage on a global basis has come an elevated attention towards constituents. It’s the law of the political jungle. If you fail to take care of your voters, you will fail to get reelected. Therefore, budget deficits and inflationary monetary policies. They have coalesced to enable the modern politician to cater to voter preferences and to take care of those economic needs.

Kevin: Trump calls it the mandate.

David: Yeah. Doing whatever it takes to support economic growth and full employment guides the bias towards loose fiscal policies, towards loose monetary policies. The risk being of course what we talked about earlier, the creation of bad money in the process. And the current US administration under President Trump has set out to rebuild the industrial base in America, drive income growth for the middle class.

Those proposed changes—we’ve talked about this before, they’re most clearly articulated by Stephen Miran—they come at the expense of a world order where previously globalization and free trade had advanced domestic consumption priorities over domestic production of goods. Now, with domestic production becoming a priority, displacing consumption, there’s an increased likelihood of US dollar devaluation as a complementary tool to the tariff regime being put in place.

Gold is catching the attention—if we’re looking at domestic policies and how this plays towards growth and gold—gold is catching the attention of a growing number of investors unsettled by the changes being implemented and uncertain as to the timeframes in which they might succeed.

So if you assume there is a successful roll-out of these policies, implementation of these policies, there is still the interim. This re-engineering of the global trade system, consistent with domestic economic priorities, it supports gold as a reliable reserve asset for those who are on a wait-and-see footing.

Kevin: And that so brings into focus globalization 2.0. What you’re talking about was dollar-based. And the way we did things was we bought things from China and they would turn around and recycle those dollars back to us. We bought things from OPEC, the OPEC nations, so they would turn around, recycle those dollars back to us. Currently, though, we have gold recycling, and dollar recycling seems to be on the fade.

David: Well, that’s right. I mean, during the ’70s when the dollar was sort of losing respectability, we introduced the petrodollar system, and OPEC essentially agreed to take proceeds from our oil purchases from the Middle East and recycle them into Treasuries. So it created a trade imbalance. We were running deficits, they were running surpluses. But the virtuous cycle for us was they would recycle those trade surpluses into our budget deficits, and they would fund our government operations by buying Treasuries.

Kevin: It was a beautiful relationship until it got too expensive.

David: And then, we’ve done the same thing with the tradeable goods sector, China being foremost in that way. So I mean, it is really interesting to see the administration suggest we’re going to re-engineer the system when I think frankly they have yet to figure out or address what happens when you’re not running trade surpluses—or other countries are not running trade surpluses and recycling those dollars into the Treasuries.

How, Mr. Bessent, do you intend to finance our deficits? How? And it’s not good enough for you to say, well, we’re not going to have deficits. I don’t believe it. I don’t believe it. And I don’t believe it because we have a democracy. I don’t believe it because, as we suggested earlier, adoption of a democratic political structure means that politicians care about the whims and fancies of their voter base.

Kevin: So it’s got to be a little worrisome, every time one of the countries goes and buys a little bit more gold instead of a little bit more Treasuries, what we’re seeing is we’re losing those people who were financing our debt.

David: Well, that’s right. So we get to gold through the lens of capital flows and trade settlement and what we would describe as the new gold recycling. Jeff Curry, who is former Goldman Sachs Head of Commodity Research and he’s now with the Carlyle Group, has observed that the nature of the 50-year petrodollar system is changing, and major commodity producers are no longer automatically recycling their dollar-denominated commodity revenues back into US Treasuries. A similar behavior is occurring with imported finished goods, where our trade surplus partners are not automatically recycling their surpluses.

Kevin: I think it’s worth you quoting word for word what he said.

David: “For the first time ever, that dollar recycling is not occurring. And what is replacing it? I call it gold recycling. It explains a lot. Why gold prices are as strong as they are. And what is the evidence of that? Is it the emerging markets? The BRIC countries all met with Saudi Arabia and other key participants in November of last year, and discussed how they’re going to trade with one another using local currencies. And then, whatever it nets out in settling, they would settle in gold. You’re unlikely to see the dollar recycling playing out, probably, ever again.”

Kevin: And he’s basically saying the petrodollar is being replaced, at least gradually.

David: Yeah. This idea of petrodollar and trade dollar recycling coming to an end has profound implications for our budget deficit financing. It has profound implications for the US dollar. It has profound implications for the gold market as well. As Curry suggests, it’s actually a new source of demand and enduring demand for gold.

So strong evidence that this is already occurring is in the commentary from Charles Gave, he runs GaveKal Research out of Hong Kong. I’ve met with Charles in his office there. But also just if you look at the ratio between gold and Treasuries, that tells its own story. And to quote Charles Gave, “If gold outperforms the dollar bull market, it means that people are starting to be worried about the US dollar. They would rather own gold than a bond giving them a yield.”

Kevin: Okay, but you’re not saying what YouTube is saying right now, which is the dollar is no longer the reserve currency. This is—

David: Patently false.

Kevin: Yeah.

David: Now—and we don’t have a second alternative. This is where you see currencies, relative to each other, grinding lower in a competitive devaluation, with savers on a global basis—roughly eight billion of them—trying to figure out how to preserve purchasing power and keep their heads above water.

This preference again for gold over Treasuries, this preference does not immediately compromise the dollar as the world’s reserve currency. It does complicate it, and it does erode its strength at the margins, but the preference by global central banks to hold more gold as a reserve asset, this has been increasing—notably since 2009, dramatically since 2022.

You’ve got reserve asset managers who are interested in the control they maintain with a physical asset like gold, different than other paper assets which are held on deposit in a digital landscape that leaves them vulnerable to seizure or sanctions—

Kevin: Like the Russians. Yeah.

David: Exactly. Just like they experienced with 300 billion dollars back in 2022, taken by the US Treasury Department. Since that event, central bank reserve asset managers have doubled their annual pace of accumulation from 500 tons a year to over a thousand tons a year. This is trust which is diminished and a new urgency being placed on control of a liquid asset outside of financial markets.

Kevin: And it is so important to look at liquidity, liquidity that— Everything changes when the liquidity dries up.

David: And in this case, we’re talking about capital flows and trade settlement and how the new gold recycling system creates support for the long-term trend in the metals.

Kevin: So that brings us back to liquidity. When liquidity is abundant, things flow a lot easier than when things get dry.

David: Yeah. Last but not least, you look at the global financial markets, and this is where we started—with the rockiness in the global financial markets following the Rose Garden discussion and announcement last week. My final observation on the strength of the gold market comes through that lens, that of the financial markets, it’s a non-correlated asset that seemed very correlated last Friday.

Kevin: Sometimes it goes up, sometimes it goes down.

David: I think we’ve explained why it was correlated in terms of the forced liquidations by hedge funds. Gold is considered a safe haven. It’s like Treasuries. During periods of market turbulence, money flows there. When liquidity is abundant, it’s risk assets that perform very well. You don’t need the safe havens. When liquidity becomes scarce, risk assets tend to suffer. Gold catches the safe haven bid, tends to outperform.

There’s no crystal ball to know precisely how the financial markets are going to perform in the years ahead. And I’ve suggested, based on charts, based on valuation metrics, that we’re heading into a secular bear market. But the important measures to be mindful of, again, are the valuation metrics and the measures of liquidity.

When you begin to see interest rates rise in the context of a broad market liquidation, it tells you that there is a tremendous amount of stress within the bond market, as well as within the equity market. Liquidity is drying up. And when you have a liquidity crisis, guess what happens next. It leads to solvency crises.

So, again, we look at the important measures being valuation metrics, measures of liquidity, and if domestic and global events create sufficient uncertainty, guess what? Liquidity tends to shrink. Risk assets tend to underperform to the degree that investors migrate to safe havens like gold, there you have a pocket of outperformance.

Kevin: So would you just say the overwhelming driver for gold last year and the last couple of years has been uncertainty, but even more so now?

David: Yeah, and I think it comes back to these broad ideas. If you see gold through the lens of currency stability, international relations, domestic policy, capital flows and trade settlement, and then how it ties and relates to the global financial markets, gold has been signaling for a number of years that we are at a very important historical inflection point. Gold surpassed a 25% return last year, rose over 19% in the first quarter of this year, and it’s signaling structural changes are occurring. Smart money has been positioning ahead of that. We still don’t know the degree to which the US dollar is going to remain strong. There is currency uncertainty.

We do have a pretty good idea that the world is changing from the viewpoint of international relations. And if you look at international relations specialists, they’re concerned that much of the post-World War II order is coming undone.

Let’s call that great geopolitical uncertainty. We have currency uncertainty, we have geopolitical uncertainty. If you look at US domestic policies being intertwined with global trade dynamics, very much a factor in geopolitical events over the next several years. Again, we’re driving uncertainty by our US domestic policy priorities. The gold recycling thesis put forward by Jeff Curry is symptomatic of an unsettled trade environment, which becomes more unsettled by the day.

But this was an idea that he put forward long before Trump took office. This was in motion. Unsettled trade was already a reality. Now, we’re negotiating around it and trying to get a better deal, and may end up breaking things and blowing things up accidentally.

But the global financial markets have remained very buoyant in light of the structural changes that are afoot. We’re likely to see that change. Last week could have been the first significant down stroke. Markets mean-revert from a valuation perspective, and they also contract in value due to shrinking liquidity. And so once again we find gold as a place that investors have traditionally flocked to.

While we have seen central bank demand increase dramatically in recent years, it is going to be the investor’s turn to address their own allocations in light of the shifting, structural, secular and systemic change.

Kevin: That’s the amazing thing. The investor hasn’t really entered the market yet. And so, let’s don’t blame Trump for everything here. I mean, we’ve been talking for the last few years about the Buffett ratio, Dave. The Buffett ratio has been screaming that the market has been overvalued at record, record levels.

David: Yeah. Let me end with the Buffett ratio. We got the March Z.1 data. That’s the report we get from the Fed. It’s only a week or two old. You take the value of corporations and divide by GDP. That’s the Buffett ratio. So the capitalization of all stocks divided by GDP, and the capitalization is currently 209% of GDP. It’s the second most expensive market in US history. Maybe it’s slightly less expensive than it was at the end of March, but this, again, just for perspective, we have begun a correction. We have just begun a correction. Measured against the Wilshire 5000, it is the most expensive market in US history at the end of March, 2025. So when I consider the necessary collapse in prices to bring that valuation metric to undervalued, I’d say we have an arduous road ahead.

Rallies, my recommendation, sell into them. Let me say it again. As we sound like a broken record, add to your metals positions, increase your cash, de-risk your portfolio, be liquid.

I’ve shared this with you in order to be candid. Last time I gave you a liquidity number, we were between 40 and 45% in our managed money portfolios. We’re now north of 50%. The dynamics that we see within the financial markets are incredibly frail. They are distinct from the economic variables which have yet to roll over. Maybe they will follow suit, but there is a tremendous amount of fragility. The bond market is communicating that. Credit default swaps are communicating that. Spreads between a variety of fixed income instruments are beginning to communicate that. What we’re looking for as confirmation of a structural bear market showing up in corporate credit has occurred.

* * *

You’ve been listening to the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. I’m Kevin Orrick, along with David McAlvany. You can find us at mcalvany.com and you can call us at 800-525-9556.

This has been the McAlvany Weekly Commentary. The views expressed should not be considered to be a solicitation or a recommendation for your investment portfolio. You should consult a professional financial advisor to assess your suitability for risk and investment. Join us again next week for a new edition of the McAlvany Weekly Commentary.