Podcast: Play in new window

About this week’s show:

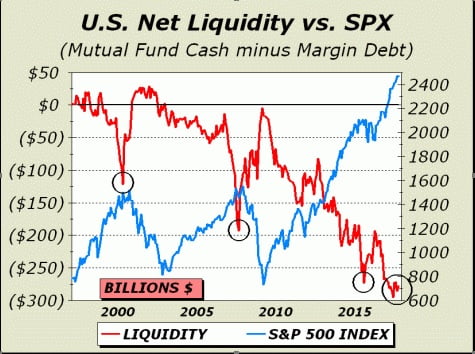

-There Is No Liquidity Left: See Chart (Credit: Alan Newman)

– Ratio of Business Revenue To Stock Price At All Time High

– Mood Investing Just Like Mood Rings… It Always Changes

The McAlvany Weekly Commentary

with David McAlvany and Kevin Orrick

“On today’s show, does the over-extended market ever have to have a correction? All indicators that have signaled a crash in the past are screaming, ‘Get out!’ Is this time different? Stay tuned.”

– Kevin Orrick

“We will be unable to finance future deficits by monetizing assets ad infinitum. And that’s the idea – that somehow we will continue to do what the Fed has done. I contend the market will revolt because we are not compliant, we lack respect, we are anything but cohesive. Increase the temperature, change the mood, and we, as the masses, will revolt.”

– David McAlvany

Kevin: David, you’ve had a pretty heavy travel schedule already, but it’s going to get heavier here come November. You and your dad are, as we have talked about before, doing seven conferences around the country, and I think it would be worth, before we even get started, repeating those locations. I highly, highly encourage anyone who can go to any of these conferences, it’s even worth traveling to if you have to fly into one.

David: It’s interesting, October is full of meetings and speeches relating to the content of the book, relating to Legacy. I just got back from Atlanta. I spoke to a private group there, and will be heading to North Carolina to do the same here in a week’s time, and then off to Idaho to do the same again. So November, you are right, is extra busy, but those are client conferences, or you may not be a client, but you are interested in knowing what Don’s views of things are, what my views of things are. And we had just a phenomenal turnout in the West Coast.

Kevin: Yes, and now you’re kicking the next round off in Kansas City.

David: That’s right. Overland Park, Kansas is November 3rd. Then we go to Minneapolis November 7th, and Philadelphia November 10th, Charlotte, North Carolina November 14th, Austin November 17th, and then November 28th we will be in Naples, Florida. And then the last one is December 1st in Orlando. So, a full conference cycle, and you are right, it is very easy to get to some of those cities, easier than others, and what we saw repeatedly is people flying in from Canada, from Mexico, Australia, and of course across the country, as well, where it was just actually as easy, or easier, given scheduling constraints, to hop on a plane and show up for an evening and consultation the next day.

Kevin: Now, we are asking for RSVPs just so that we know how many are coming. We need to know how many chairs to set up and how much snacks and food to buy. We would just ask that everyone give us a call here at the office, 800-525-9556. Not only will we be taking RSVPs for the conference, but the following day after each conference, you and your dad privately meet with people who would like to just sit down and talk to you for a few minutes.

David: Right, to brainstorm just about anything. We have folks that want us to do some consulting relating to personal and business matters, intergenerational planning, business legacy planning, and sort of a handing of the reins from one generation to the next. We have people who want to talk about risk mitigation in their portfolio. We have folks that want to visit with us about precious metals or what we do in the asset management business on the short side of the market with Doug Noland – everything under the sun.

Kevin: I even have clients who are coming in because they have either family members or kids who are in missions and want to sit down and talk to Don about the orphanages and some of the avenues of getting into missions work.

David: That’s right. Don is back after ten years of being in Asia to do this conference cycle, as he did on the West Coast. He is very excited about it. He loves what is happening in the markets. You just have to spend some time with him to see his sense of urgency and energy relating to these things. The October newsletter that he just wrote will be one that we hand out there, and it is a fabulous read. So I look forward to having everyone come out and spending some one-on-one time with you.

Kevin: Dave, one of our favorite guests, a man named Tomas Sedlacek, who was the economic advisor to Vaclav Havel, had come from a Communist background, he had moved into a free market background, but he gave us an amazing view of how an economy needs to expand at some times, and sometimes shrink. You go through rises, you go through falls, very much like a sleep cycle. I’m two weeks back now from the Israel/Jordan trip that I took, and I’ll tell you, it took most of those two weeks for my body to react, as far as the jet lag and the loss of sleep coming back. I’m thinking, these markets are very much the same. If you don’t give a market some sort of sleep cycle, then it ultimately will completely destroy itself.

David: Right. Reversion to the mean is something that is very common, and folks on Wall Street know what that looks like and what that means. When you look at the markets it’s a little bit like a living organism. They push and they press and they’re active. And then they pause, and they repair and they rest. Without those ebbs and flows and the very important reparative work, you have stresses that build, and of course, there are the requirements of excess stimulants to keep things going, to keep them going ever higher. A story comes to mind. My dad once knew a CIA operative who for several years had assignments that required him to go and work for a week or ten days uninterrupted without sleep.

Kevin: Can you imagine that?

David: The reparative work was not done, and in the normal cycle of activity and then slumber he had to manipulate that in order to get done what needed to get done. I think it’s a possibility to sustain that kind of a grueling pace for very short seasons.

Kevin: If you’re Jason Bourne. Maybe.

David: Right. But here, it did ultimately catch up with him, and I don’t know all the ins and outs of Parkinson’s disease, but he died of Parkinson’s, a nervous system disorder, and it is certainly tied to environmental, as well as genetic factors.

Kevin: Let’s look at the market, Dave. The market – I’ve never seen anything like this in my entire life, where you see the stock market just continually going up without any kind of correction whatsoever.

David: Yes, there are very few periods of time like the present. So, it’s easy to step into yesterday, or the day before, or the day before that. The market seems to always go up. And if that is your timeframe, the last three days, the last three months, or even the last three years, you have to know that there are periods of reparative work which need to occur, and that really hasn’t occurred for nearly a decade.

Kevin: We’re not even getting minor corrections right.

David: That’s right, you look at the S&P 500 and we haven’t had even a 3% decline in over 230 trading days. This week we will exceed the record, I think 241 trading days, which has been held for 20 years. Today we have big trades. The big trades are buying FANGS – Facebook, Netflix, Google – the things like that.

Kevin: Let’s look at the volatility index. You can look at stocks and see them continually rising, but when the volatility index falls to almost zero, and it’s pretty close, then you realize that no one thinks that there is any risk of a correction even in the future.

David: And just to see how confident that trade is, the other big trade, other than the FANGS, is shorting volatility, or shorting the volatility index, believing that you go from a low level of, say, 9½ to 10, and it will go even lower.

Kevin: So you can play that bet, too. You can play the bet that volatility will actually drop.

David: That’s right. Now, the VIX is still, as I said, in single digits. If you remember, from last week we talked about the decline in U.S. mint sales of gold and silver coins. Interestingly, the last time we saw sales at those levels, as low as they are, the VIX was also at the kinds of levels that we have.

Kevin: Wasn’t that right before the last big crash?

David: It was months before the market collapsed. The guys at Golden Rule Radio pointed that out this week. And what it says is that complacency shows up in the VIX, it shows up in the volatility index, and it also shows up in gold purchases, as much as concern shows up in both of those places on the other side of the pendulum swing. So again, you have reversion to the mean, or if you want to picture a pendulum, we go from one end to the other and you have that midpoint right in the middle.

Why don’t we stay at the mean in the market? Why don’t we stay at fair value in the market? Because it’s not the way the market works. You go from extremes of greed to fear and back again. And when you have the Volatility Index level you have gold selling, or not selling at all. Again, these are indications of where the pendulum is. It tells you exactly where we are, and in some respects tells you exactly what is going to happen next.

Kevin: I think it should be noted that even though physical gold, coin sales, are down here in America, the actual inflows to ETFs that invest in gold, some of the bigger investors in gold are the ETFs, there are inflows, not outflows. This is one of the things that is affecting the price to the upside.

David: That’s right. In every year where ETF gold and silver flows have been positive, you end up seeing an increase in the price of the metal. It has been that way going back to when those ETFs were launched in 2004. And so, what we need to see to move the price needle is investor money moving into the metals. We’re not seeing as much moving into the physical coin market, but we are still seeing healthy flows into the ETFs. It was the years of 2012-2015 where you had outflows, and those were down years for gold. Every other year since 2004, net inflows into the ETFs were positive years for price action in gold. We are presently on track for that. We’re still up around 10% for the year. It’s interesting, because I compare that to what is happening in other markets.

Kevin: Look at the NASDAQ, Dave. Some of these markets, you can give it a name, but it’s not even a resemblance of what the market was, say, 20 years ago. The stocks that are going up right now in the NASDAQ, I don’t think a lot of them even existed before the last big NASDAQ crash, which was 2000.

David: You’re right, particularly if you carve out the NASDAQ 100 and the guys who have been driving prices higher. The names that are pulling the indexes higher, they weren’t even publicly traded companies in the year 2000. This is a fascinating realization because as the NASDAQ hits new highs, you look back at the highs of 2000 and it’s not the same players. In fact, the games that were played in 1998-1999 as we got to the tech bubble boom and then ultimately the bust, those companies, the participants, are still about 50% below their peak value. How is that possible if the NASDAQ is reaching all-time highs, how do you have an index at all-time highs with the old participants at half their previous value?

Kevin: Which shows that you really never had a recovery in those stocks.

David: Not like you would hope. This is the reality.

Kevin: I wasn’t born during World War II, but I know that the command and control economy was in full force at that time. When we went to war the government took over the economy, including stocks. They went in and worked with interest rates, what have you. We haven’t really seen anything since that time, but now we have the central bankers doing the same thing.

David: From the perspective of market history, you’re right, very limited timeframes in which the government was that actively involved, so the command and control days were 1942 to 1949, maybe stretch that to 1951 if you’re talking about interest rates, but 1949 if you’re talking about the capital markets opening up and investors coming back into the market, because frankly, nobody was going to invest in the context of government controlling things.

Kevin: But we were at war. Probably, desperate times call for desperate measures.

David: We were at war. You had the cost of production, which they were wanting to control. The price of commodities was controlled. Interest rates were held artificially low through the period so that the cost of financing war and the debt that was being accumulated would be manageable. And we know that natural effects of war were in that timeframe suspended. But they were suspended only for a time because inflation was tempered by the D.C. elites. We’re talking about elected and non-elected officials who were doing victory laps for keeping greater prosperity through the war period, although ask anyone who lived through the timeframe, and rationing and price controls and things were actually quite difficult to deal with because it wasn’t reality.

Kevin: Yes, and when you take reality out there is always a cost, is there not?

David: All things come at a cost, so you had the repricing which began again in the period of 1949 in the asset prices of stocks, and then in the fixed income market when, really, they got off of the scale, so to say, and were not influencing the market, that is, the Fed and the Treasury together. And so, importantly, it was interest rates which moved higher, and inflation which began moving higher once supply and demand and the price mechanism were allowed to function again without governmental interference.

Kevin: But we were at war. This time it’s different. We’re not at war, Dave.

David: Presently, it is interesting and it is important, because it is the only other period in U.S. history where the masters of the universe, central bankers this time, replacing the office of price administration which was started in 1941 by Executive Order, again, for time constraints and things of that nature. But this time it is the central banks rather than the D.C. power players who are managing prices and setting rates at below market levels. And they focused on influencing the financial markets by controlling the credit spigot. And again, they’re doing it with credit rather than what they did in that war period, which was setting the price of beef, deciding what you would have to pay and could charge for coal or oil or gasoline. It is increased flows of credit, and it’s suppressed borrowing costs, which are their tools, the modern day tools, for price controlling. And they have, predictably, altered investor behavior. That’s what they have done.

Kevin: Right. Well, nobody is concerned about risk if they know that the government has their back.

David: Reducing the conscious concerns of risk and are promoting the search – I think, actually, I’d rather say they’re creating a mad scramble for higher yields. And the temptation is real. It is a real temptation for any investor to say, “I’m just so tired of zero, or 2, or 3, or 5. Where can I find 5, or 6, or 7, or 8 percent?”

Kevin: This time is different, though, Dave. We were talking hundreds of millions, maybe billions of dollars that were affected back in the 1940s. We are talking trillions and trillions and trillions of dollars at this point.

David: At no time in world history, in investment market history, has stretching for yield ever ended well. Never. Not once. So, the kind of behavior that we see today is the kind of behavior that precedes pain. It is what precedes regret. And in the moment, what you have is the need and the solution. So it’s a scratch and an itch combined, and you solve your own problem, but you don’t realize that something else is going on, and it’s a context issue. So you’re right, they are dangerous times because we’re talking about trillions of dollars marching to the beat of the Fed drummer. And it’s not a problem until it’s a problem. You have the extended use of stimulants to keep things going, and it’s unparalleled.

Kevin: But you look at the behavior changes, Dave. You and I were in Argentina just a couple of years ago, and they had 40-50% inflation. We knew the history of Argentina, that they had defaulted on their debt – what was it – six, seven, eight times. And right now, you have people who are lining up and begging for Argentinian bonds.

David: Understandably, the Kirchners are gone, so the era which brought so much pain starting in 2001 and all throughout the early part of this millennium, 194-year history of the country, they have defaulted eight times. The reality is, the folks who are in office today will not be in office tomorrow, and just like any good politician, it is always a question of aligning interests, and how will you get elected if you don’t pad people’s pockets? That is the problem that politicians face is that you have to find constituents that will vote for you and promise them something.

And in Argentina they have perfected it. So we have a cleaned up mode, but a 100-year Argentinian bond offered this year and over-subscribed 3½ times says that people don’t remember the eight defaults in 194 years. They think that it is different this time. And a part of the stretch for yield, going for something that yields between 7% and 8%, 100-year bonds, again, why are you ignoring risk? You’re solving the income problem, but you’re justifying greater risk to do it. And any time you’re taking greater risk, it’s not just theoretical. You can say, “Well, what are probabilities, if I’m increasing my risk X, Y and Z percent? But still, how is it going to hurt me? The odds are so low.”

I think to myself, the things that I see happen in an environment like this, people will regret. Will the gentleman who paid over $650,000 for a parking spot in Hong Kong, and consistently the prices have been edging toward $500,000 for a parking spot in Hong Kong – are there going to be regrets? Is that a symptom of funny money and excess liquidity in the marketplace driving everything like crazy, or is that just the new reality?

Kevin: You were talking about price setting, both in World War II and now, in a way, with the central banks. When you change the price of something you destroy the ability to compare it to something else. You have brought this out before that Italian bonds actually were selling at a rate that showed them to be safer than a U.S. Treasury bill. That’s incredible. We have this thing going on with Spain right now and you have people who really don’t react at all as if there is any kind of fear. When you can’t compare gold versus an ethereal type of thing like bitcoin, or when you can’t compare what a parking place should be in Hong Kong or an Italian bond versus a treasury bill, what do you do? At that point, you look like a fool unless you’re getting the best rate.

David: Yes, so relative value is ultimately very important, and that is what you are losing. You are losing comparability. I think comparability is key to the assessment of risk. You have credit spreads which, again, are the difference between two different fixed income instruments, and it tells you the expansion and contraction of the spreads, the difference between them gives you this relative risk evaluation. But when you start tinkering with credit, tinkering with the spreads, tinkering with, ultimately, the prices of assets, you don’t really know what you’re looking at. Looking at the risk of investment option A versus investment option B, and this is one of the casualties of our current command and control dynamics.

Kevin: People are getting free money. When there is no cost to money, Dave, who cares what something costs?

David: That’s right. You remove the cost of money and it increases access to money, and it decreases the normal screening process for who gets how much, and at what cost. We saw that happen in 2004, 2005, and 2006 as Greenspan passed the baton to Bernanke and there was this push to create the housing bubble. And they did a good job of that, but one of the ways that they did that was by diminishing the way risk was assessed. In fact, they just said, “Money for all. It doesn’t matter if you can fog a mirror.”

These are the ninja loans. These are the liar loans. These are the things that we, in retrospect, say, “Well, that was so obvious.” And yet people tend to ignore the obvious in favor of having their needs met. It is really interesting – banks, Wall Street firms, prime brokers, anybody in the business of finance appraises risk with care, typically, particularly when capital has a cost.

Kevin: Right, when there is an interest rate to pay if you are borrowing money.

David: Because it tells you what your hurdle is. “We have to pay this back. This is the cost to get this money, and here is what we are going to do with it.” But you recognize a cost. You don’t weigh what you’re going to do with it in the same way when there is no cost to it. So the cost of capital is very interesting in terms of the way that banks, Wall Street firms, prime brokers, appraise risk. It is not really the case when money is free. And central bank communications from Draghi and Yellen and others echo the same refrain, which is, “We got this.”

Kevin: Right. “We’ve got your back. Don’t worry about it. “

David: “We’re going to do whatever it takes.” Or, “There isn’t going to be a decline in prices on my watch.”

Kevin: So, let’s short the VIX, Dave.

David: I think Yellen actually said, “Not in my lifetime.”

Kevin: (laughs)

David: In other words, we’re not going to have a decline in prices in my lifetime – just for historical context, do you know how presumptuous that is? In life, you have to know what you know, and what you don’t know. And what that says is that she knows everything in the universe, right? That’s like Madame Marie O’Hare in a classic debate about the existence or non-existence of God – she was an atheist – and the question was asked to her, “So, if God does not exist, what percentage of the world or the universe’s knowledge do you believe you have?” And she said, “At least 10%,” which is a pretty large number, when you think about it.

Kevin: Of the entire universe, yes.

David: That’s right. And the debater on the other side said, “But perhaps the existence of God is that information in the other 90% that you don’t have.” I think of the presumption of knowledge and the confidence that central bankers have today, and it is such a fiction. From a different vantage point, look at it this way. Does anyone managing a business today, or analyzing publicly traded companies, as an analyst, do you know what the proper hurdle rate is for capital allocation decisions?

Kevin: No. You can’t.

David: How do you budget? How do you analyze a company when the rates that you would use to discount cash flows are a fairy tale? What are you basing it on? What are you basing values on and future projections on? What assumptions are you working off of in a realm of controlled rates?

Kevin: But what we’re seeing, Dave, and we’ve seen this before, we’ve seen this a number of times.

David: This is why asset prices bubble higher.

Kevin: But they bubble higher only as long as there is liquidity. And what we’re seeing – we’ve seen this before every crash – and I know we sound like a broken record, but we’re seeing it right now again. Let’s take a mutual fund as an example. A mutual fund has a certain amount that they have invested, and just like most businesses, they have a cash account. Or even homes – I have a certain amount of money that I keep in the bank so that if the roof leaks, or if I have bills that are a little above what my normal monthly bills would be, I have something that I can pay that out with.

Now, a mutual fund has that, as well. Sometimes it is 7%, sometimes it is 8%, 9%, 10% of their assets. Maybe it’s 5%. At this point, the mutual funds, these funds that hold stocks or other types of investments, they have virtually no extra liquidity. If anybody comes to them and says, “Hey, I’d like to cash out. I need to go buy a house with the money,” they literally have to sell their assets to do it. They don’t have cash waiting.

David: The household, as you mentioned, that has concerns, you reserve in light of those concerns, and if you’re knee-deep in clover and cash flow is no problem, then reserving is not really a big deal. You don’t even think about it, because you know that next month’s income is going to do X, Y and Z for you, and it replaces itself and there is really no reason to have it just sitting there in the bank, particularly in a zero-rate environment where it is not earning anything. So reserving is tied to concerns, and you will see mutual fund managers, as they have growing concerns in the market, tend to reserve more or less. Interesting dynamics, though, at the end of a market cycle, where investors are pressing for returns and competition gets really steep between asset management.

Kevin: These guys throw it into the market because they can’t earn anything on the cash that they keep.

David: Out of 100% of a portfolio, if you’re trying to match the performance of an index, and you have some percentage which is not in the market, let’s say you’re 30% cash, that means your 70% has to do the work of 100% and the only way you can do that is by taking outsized risk, or leveraging, or something like that. So, what it means is, if you’re going to reserve at all as a mutual fund manager, you are going to under-perform and you’re going to get fired, which means mutual fund managers are entirely in that fashion pro-cyclical. They are willing to play the game, and even if they do have personal concerns, you run with the bulls. You have to run with the bulls. You have Wells Fargo, Bank of America, including our Commentary guests – everyone – Alan Newman I’m thinking of – they point to low levels of cash and liquidity in the market today.

Kevin: I saw that chart, Dave, from Alan Newman. We’ll post that on the website.

David: Absolutely.

Kevin: So, for the listener who can click on the link, look at that chart. It shows every single time that we hit these levels we have a crash. This time, however, we hit a low level and the Fed continued to push the market up, and now we’re hitting a new low that we’ve never seen before.

David: That’s right. It indicates a fully invested community.

Kevin: Exactly.

David: An added wrinkle in this period is that trillions of dollars have migrated from actively managed mutual funds to passive ETFs. You say, “Well, then maybe there is just no problem with looking at liquidity constraints, or limits, or whatever, in mutual funds.”

Kevin: Well, talk about redemptions in ETFs then, Dave.

David: This is the bigger deal, because there is no cash cushion in an ETF. When someone redeems shares in a mutual fund there is some cash, even if it is a low percentage – 1%, 2%, 3%, 4%, 5% of cash – in that pool of assets.

Kevin: In an ETF, it is fully invested in whatever asset it ways it represents, right?

David: So the dynamic is this. Someone liquidates shares in a mutual fund, and the first redemption is not a forced sale of stock, it comes from cash. So you may not create negative pressure on the asset in question, but when you’re dealing with an ETF there is no cash cushion, and it means that any liquidation triggers an immediate pressure in the market for the assets that are in that ETF. And of course, it is proportional to the assets, usually on a cap-weighted basis. So the redemption dynamic is radically different. And I think we’re going to see some really fabulous fireworks in the ETF market because of this.

Again, fund managements teams – if they raise cash levels in a rising market, you know what happens? They get fired, because under-performance of the index gets them fired. So they take more risks because the clients are demanding more risk, and clients expect more than the index returns, or they would just buy an index. Everyone wants to be 100% allocated in a rising market.

Kevin: And vice-versa.

David: Everyone wants out in a falling market. So it’s an all or nothing game. And it’s funny because what we’re really talking about is investor herding. And it’s a remarkable feature, in both a bull market and a bear market – all or nothing. Herding – everybody does the same thing at the same time. No one has the ability to think outside of the group.

Kevin: You have just been talking over the last couple of days to people who are actively involved in real estate. Some of it is real estate speculation. We all know when a real estate market is really hot, the best thing to do is just leverage, and leverage, and leverage. You buy something, you leverage it. You buy something, you leverage it. If that market is rising, that is a 100% accurate formula for making money. The problem is, when it falls, that leverage can just crush you, like we saw back in 2006.

David: It doesn’t matter the asset class, if prices are rising. If it’s a local real estate market, what’s the attitude? Leverage up. Buy another. Between appreciation and income, you can justify it. That’s what goes through the mind of the investor. Unless you’re wrong about one of those elements. Appreciation doesn’t come as fast, or it doesn’t cash flow the way you thought it would. Or there are repairs in elements that require you to put even more money in. People seem to be stuck in the cycle they’re in, unable to see beyond the present, and peer into the future.

Kevin: And then they call it a black swan. “We couldn’t have seen it coming.”

David: But the past is prologue. Think about that – the past is prologue. Cyclicality is as sure as night following day. So, are you positioning for the next cycle? For most investors, it is doubtful. Too many investors need the affirmation of peers. This is not new. J.R. McCulloch, in The Principles of Political Economy wrote this from his perch in London in 1830. “In speculation, as in most other things, one individual derives confidence from another. Such a one purchases or sells, not because he had any really accurate information as to the state of demand and supply, but because someone else has done so before him.” The affirmation of your peers – too many investors, as we discussed last week, want to invest in a momentum trade. Too few investors are willing to put in the work to be a value investor.

Kevin: And the value investor is not where everybody else is. He has to be ahead of, or behind, the crowd.

David: In some respects, it is looking for quality in an area that is already discarded or considered refuse. I sat with a couple in Atlanta earlier this week. Great meeting with the Keller-Williams real estate group – 50-70 people. We were there to talk about legacy and other topics from the book that I wrote. By the way, Christmas is coming – buy a box, get a discount. If you go to our website, davidmcalvany.com – that’s the blog website for the book and things, you can buy them radically discounted. Buy one copy from Amazon – fantastic. Buy a box and you get them, I think, basically, 50% off.

Anyway, I was talking to this couple. We had just finished the conference, and legacy was the topic that I was invited to come and speak on. And I think this whole group is, in fact, trying to see the cycles of interest rates and prices and get into the next cycle now.

Kevin: So, in other words, they’re value investors.

David: They’re trying to anticipate as best they can. I spoke with a gal, and she and her husband knew the area well – Atlanta, Macon, everything in between – and her comment was, “Of course you make money on the asset when you buy it. That’s a value investor.” The momentum investor is attempting to make money based on future price, regardless and without respect for present pricing. And to the momentum investor, prices are trending higher and that’s all they need to know. For the value investor, actually, prices are not trending higher. They’re ugly. And that’s where they are most interested because they know they make money when they buy it. It’s a totally different approach to investing. Facts today suggest that stocks are expensive. How expensive? In some measures, they are the most expensive in all of market history. Revenues are a pretty decent tale, a pretty decent story, as to what is going on with a company.

Kevin: And a revenue is just simply, how much is the company bringing in?

David: Right. Kind of hard to fudge that. Hard to fudge a sales number. When it comes to earnings, because of the way they count earnings, because of the way it can be done, you can make earnings sing any song you want. But revenue doesn’t really lie. Revenues of a business tell the tale that you want to know. What would you say if I told you the price of shares compared to revenues for the S&P 500 was the highest in recorded history?

Kevin: It doesn’t sound like value to me. If it’s the highest in recorded history, that matches what we’re seeing, Dave. There is no sleep cycle at this point. It doesn’t matter what the revenues are. The stocks are just going up because “Joe over here, or Mary over here, bought a stock and I’m going to buy it, too.”

David: On other measures, you have the markets, which are nearly as expensive as each of the prior mega bubbles, the 1920s leading to the 1929 crash, it’s the tech boom leading to the 2000-2001 bust, and the 2007-2008 decline. All of those, you saw the valuations in the stock market reach peaks, and again, on some measures we’ve already surpassed them. On others, we’re getting ready to. Yet prices rise, and they confirm the decision by many to buy and to continue to buy.

Kevin: Of course, because the price is rising.

David: They must be right, because prices just went up and that gives us confirmation that the purchase we made was perfect. Kevin, one of my biggest losses as an investor was between 2000 and 2001. So one of the reasons why these mega bubbles mean something to me, and one of the reasons why I’m particularly sensitive to momentum, is that in my investment journal where I write down the things that I’ve done well, and the things that I’ve done poorly. Where I learn my greatest lessons is in the things that I’ve done poorly.

Kevin: That reminds me, I was talking to Jim Deeds yesterday, and he said the same thing again. He said, “Kevin, you will always learn more from your mistakes if you pay attention.”

David: You have to reflect on them. It’s not just, excuse them and make them go away. When you make mistakes in relationships, you know what happens most often? Our egos are so frail, we don’t allow ourselves to own our contribution. That happens all the time. Do you know how costly it is to relationship to not own it, to not learn from the mistakes you’ve made? If you are so foolish to not learn while you’re paying tuition in the world of investment, you don’t deserve to be an investor, frankly.

So 2000-2001, I placed money with a group called Inside Capital. Momentum was the game, and I loved what they did because the results were better than any other manager I worked with. I worked with six or seven different managers. And at the time, my only real measure of importance, or success, was what was going on with the price. Is it going up? And it did, until it didn’t. And I’m telling you, it was expensive tuition as a young investor. I thought this whole group knew more than I did, and they did in some respects, but I shopped and found them on the basis of returns. And I got precisely what I deserved. It was my first six-figure loss.

Kevin: Oh, that’s painful.

David: So the downturn in 2000 convinced me that I wanted to learn and I wanted to grow, and no longer was I going to delegate the investment process to others. I learned the hard way about blind trending and momentum. What goes up must come down. And when it comes down, it typically comes down a lot faster than it goes up. So for all those happy months and quarters when I looked at those reports and it was positive, literally, in a three to six-month period we wiped out two years’ worth of gains. It’s fascinating. And those two years of gains were explosive. We’re talking 70-100% returns per year. There was momentum. It was the tech stock boom. It is fascinating, because you look at the JDS Uniphases, you look at the CYSCO Systems, you look at companies that traded at 160 and went to 8, that literally lost 80-90% of their value. And the conversation, Kevin, 1999 and 2000, is that these are companies that will never go away. And as we mentioned earlier, actually, those are the companies that are still about 50% below their peak numbers in 2000. And the only reason the NASDAQ and the NAS100 are higher is because there are new names, new ideas, new companies. And guess what replaces the old? Guess what happens in every business cycle? Guess what? There will be something other than Facebook, other than Netflix. You don’t have the imagination for it. And what you assume will be here tomorrow – well get ready. Sometimes it doesn’t last the day.

Kevin: Just listening to you here, and talking to Jim yesterday, makes me think – you need to be honest. You had likened investing to a relationship. You have to be honest in a relationship. You have to be honest with yourself. Why did I say what I just now said? Or why do I want to say what I’m about to say? The same question could be applied to investing. You have to look, and say, “Do I know why I want to do this? What is the reason behind it? Am I doing it because I see someone, a friend of mine, who is making an awful lot of money in this particular sector? Or is there real value in this, even if nobody knows it but myself?”

David: I don’t mean to be overly critical, but it seems to me that 90% of the country is invested in something, but there is only about 10% of the population which is self-reflective. Maybe it’s 1% (laughs). But self-reflection is a part of being a successful investor, and it means that the vast majority of investors don’t have what it takes to succeed. Do you know why you do what you do? And if you don’t – is what you’re doing dependent on the mood of the market?

That gal I spoke of earlier from Atlanta – real estate is not cheap. It is harder and harder to make money in it on the purchase side. Opportunities – I’m interested, I’m always searching for. Ideally, you know what I buy today? I buy public storage units with great cash flow. You know what the problem is? They trade at 5-7 caps. That is, the rate of return that you have on them is ridiculously low relative to what they have traded at historically – 20-30% returns. Now you’re in the 5% range, and you’re moving into illiquid assets that do have the ability to have the value of the asset, itself, cut by a third, cut by half. So those special use real estate deals are priced for perfection.

Apartment complexes – if you work hard to find a great deal you might settle in a 7 cap with a lot of debt in the deal. Guess what? That same deal 10-15 years ago was a 12-15 cap. And that was before the rise in rents we have seen. By the way, rent inflation has been at the highest rate in 30 years beginning in 2010.

Kevin: And yet the returns for the landlord have been dropping.

David: The returns have been dropping because the prices have continued to rise commensurate with the rise in rents. It means that what you’re paying and what you’re getting for what you’re paying, is at the outer edge of safe. To get a decent rate of return in many real estate assets, you are now taking risks that you probably shouldn’t take.

Kevin: When you talk about a 5 cap or a 7 cap, what you are talking about is the rate of interest that you are going to earn and, frankly, the value of that real estate, if it falls at all, will probably fall greater than 5%, greater than 7%. So what you are talking about is, you just don’t want to be leveraged. You can own real estate. Let’s say that you own it outright and you have absolutely no debt on it. At that point you can say, “All right, I could manage a downturn.”

David: Actually, I had a conversation with a gal at this conference – a young gal who has bought a rental property, is pretty excited, is a broker, is doing well, and is kind of interested in how she should shape her financial future. Her question to me was, what do you think about college savings? And I said, “I hate it. I think it’s a terrible idea. It’s an utter waste of money. Why would you save money, put it in a pot, and then blow everything in the pot?” Do what you’re doing already now. Buy three or four rental properties and allow the income from those rental properties to offset the cost of tuition.

And then guess what you’ve also done? You’ve set yourself up for continuing the same theme into retirement.” And she said, “Oh, well, that’s interesting.” I said, “But be careful that you don’t buy too much, too soon. Because if you have too much debt you assume that you can rent it out, but you have to assume, you must assume that you carry the cost without a renter. And how many pieces of property can you actually control with no renters?”

One of my classic conversations with a client we’ve had for years and years and years, and unfortunately passed away not too long ago, was a gentleman who made his first fortune selling houses in the 1930s, $3000 to $4000 per unit. He went on to own outright, not a dollar of debt, 750 apartment units in the downtown San Francisco area. He started with 100, then it was 200, and then it was 500, and then it was 750.

And the question was, how did you grow like that? He said, “Well, I didn’t have any debt, and as prices invariably turned down because business cycles do ebb and flow, the competition who was heavily leveraged would see their properties foreclosed on because there was too much outflow and not enough inflow, and the vacancies were too great for them and they lost the property.

Kevin: It reminds me of the client that stood up in Portland and gave his testimony that your dad had told him to sell before the 2006 crash and he sold all of his real estate and then was able to come in at 35 cents on the dollar and rebuy it because the crash had come.

David: Yes, and into some of the same properties that he had owned, which is fascinating.

Kevin: So you have to look for cyclicality.

David: Yes, I think anyone with a past-is-prologue perspective, that is, anyone with a memory of markets and their cyclicality, has to be concerned about current values. Finding good value is nearly impossible today – nearly. There are special situations, there are shifts in use, they do exist. But we’re in an era of capital price controls, and we’re in an era without historical precedent, so allocating capital in this kind of an era is very interesting. And I would say, actually, very dangerous, again, in the sense that you don’t know what happens next. No one knows, including the central bankers, what happens next. Price controls without historical precedent. We have the temporary measures of intervention – “temporary,” because they’re still with us after nearly a decade. I think, to a younger investor base who don’t even know what this monetary backdrop represents – they think it’s normal because it’s all they’ve ever known. All they know is the mood of the market, and the central banks have done a great job influencing the mood. I still contend that mean reversion is either your best friend or your worst enemy. Mean reversion tends to multiply wealth off of low levels, or it divides, it cuts in half if you’re starting at historically high levels. So mean reversion is not something to be afraid of, you just have to know where you are and where the pendulum is. Don’t be on the wrong side of the swing.

Kevin: You were talking about giving your feedback as to whether you made a good investment or not, as to whether it was rising, and it turned into a six-figure loss for you. So vice-versa, the same thing. An investment does not have to rise for you to be right. Also, if you’re owning a falling investment, you may still be right.

David: The best evidence of being wrong in an investment when the investment world is at price action – price moving against you…

Kevin: Not always.

David: I think sometimes it is. Maybe it is. As a trader, if you’re day trading you have a different kind of time perspective, and if you’re wrong in a nanosecond you may be wrong in a minute, too, and you might be wrong for the day.

Kevin: But if you’re a value investor you have to expect that, probably, what you bought is going to go down for a little while more before it turns around.

David: That’s right. I spoke to a gentleman who, as a banker, as a CPA, joined a bank committee, and was responsible for buying distressed debt. Fascinating guy – mountain climber. Fascinating, fascinating guy. An amazing human being. He would buy distressed debt. He would usually buy it at 30 cents on the dollar and then watch it go to 10-15 cents on the dollar. And because he was on the bank investment committee, they bought it before the paper was literally dying, and because they were on the investment committee, had to hold it for several years without price discovery. But he would buy it at 30-40 cents on the dollar, watch it go to 15-20 cents on the dollar, and then sell it at 80-90 cents on the dollar.

Kevin: It takes resolve and patience.

David: So let’s say you’re shorting tech stocks in the late 1990s because valuations are eye-popping. You look and say, “I’m not paying for 50 years of earnings up front. I’m not paying for 500 years of earnings up front, or an infinite number in the case of a company losing money, but still selling with a multi-billion dollar market cap. Prices rise inexplicably beyond fair value when greed is driving the allocation decisions. And prices, if you can recall this from a distant era, if you have, again, that idea that past is prologue, they also decline well below fair value when fear is driving the allocation process.

So depending on mood in the market, you may look silly for some time. Again, back to that question of, it’s the best evidence of being wrong in the investment world if the price is moving against you. Mood is driving prices.

Kevin: And mood is not value investing.

David: Is mood even reality? How you feel about something in the moment – yes or no? Maybe it’s yes and no. There is a certain reality, but it’s limited. Mood is the present sense of things, which may or may not be based on fact. I think that’s fair, don’t you think?

Kevin: Again, like you, we’re talking about markets. Markets have moods. Relationships have moods, and you have to be careful. What is the reason I’m saying what I’m saying right now.

David: Right. Mood sways us in relationships. Mood impacts our view of work, of whether we enjoy it or not. Mood is, unfortunately, very fickle, and it can be highly subjective. And it is vulnerable to radical shifts on very short notice based on a constant change of inputs, data and experience. So mood, if that’s what you’re basing your investment on, or success on, how you feel and what it is doing in the moment – I don’t think one should ever make relationship decisions on the basis of mood. You are likely to regret it, or be likely to construct a supporting narrative from that creative part of your brain as to why you do what you do.

Kevin: That’s right. Investors may feel optimistic, and while the price is rising, what we were about with this affirmation, they will go out and buy more.

David: And they may also feel, on the other extreme of things, like they’ve made a mistake, if prices decline right after they bought it. Which raises the question – what did they know prior to the purchase versus what did they believe, or hope, or feel? Facts may suggest an opportunity. Price action may not be supportive of the facts for some time. And the question is, can you deal with it?

Kevin: Even the experts right now are looking at this, and the ones that are realistically asking the value question, right now they don’t know what to invest in because they’re saying, “Why on earth would they allocate capital into a system that is this distorted?”

David: You see things like this – Tesla said in the third quarter they were going to deliver 1500 of – I forget which model – to the market. They delivered 80% under what was expected. They produced 260 instead of 1500. Market dropped. You know what? By the end of the day, the share price of Tesla was in positive territory again. You can disappoint and not do what you say you are going to do, not show the profit that you said you were going to show, and in this market environment it doesn’t matter. No one cares about what you said you were going to do, no one cares about delivery. So you have an old portfolio manager, Bob Rodriguez – he was an analyst and portfolio manager for years, retired now. He asked this question. “Why on earth should I allocate capital into a system where the scales are completely manipulated, price discovery is distorted, and the Fed doesn’t have a clue what’s going on? They’ve missed every economic forecast for the last nine years straight. Why would anybody pay attention to what those people are doing?” I think that’s a good question, Bob. The Fed drumbeat, nevertheless, still holds sway, the mood remains positive – Dow, S&P, NASDAQ – everything moves higher.

Kevin: Dave, just as I was leaving the house this morning, I was talking to my wife and I said, “You know, this is an unusual time. I have very intelligent people asking me if maybe there is no reason for gold again, and maybe if bitcoin is the new gold, and why would the stock market fall? The Federal Reserve has their back.” These are intelligent people who are asking what they think is an intelligent question, but what they are really saying is, “This time it’s different.”

David: That’s right. The answer that I’m hearing more and more often, as asset prices are bubbling higher, from people that actually know better, is exactly what you’re saying, that this time this is different. And I look and I think, “Okay, well, maybe we can finance it infinitely.” The object lesson everyone points to – “No, it works differently in Japan. Look, they’ve got debt-to-GDP figures north of 250%, we’re only at 105-110%. We can expand and continue to grow the economy and debt doesn’t matter anymore because, again, we’ve figured it all out.”

I just think, “Look, the Japanese experiment with monetary policy? They have maintained ever-higher levels of debt since the crisis in 1990, and you’re right, they have not suffered for it, as many analysts thought that they would. But consider the cultural differences between Europe and Japan. Differences – not one better than the other, but just different. Consider the cultural differences between the U.S. and Japan. The Japanese are cohesive. They’re culture is one of respect. It is one of compliance, even one, broadly speaking, throughout Asia, but particularly in Japan, too, one of shame. You don’t do what you’re not supposed to do, and you do what you are expected to do.

So look at our election cycle, Kevin. The 2016 election and the reaction to the Trump Administration since – our people are wired differently. Look at Brexit – it’s different. Look at the Macron election in France – it’s different. Although Le Pen did not win, and that was sort of the “populist” vote in France, think about what did happen. Two dominant parties were completely cast aside for a third party that only came into existence a short time before the election, with a candidate that had never held public office! Think of that. What is that? That is a repudiation of the status quo. That is not Japan. Culturally, we should never expect to duplicate something that requires a unique set of variables to work.

We will be unable to finance future deficits by monetizing assets ad infinitum. And that is the idea, that somehow we will continue to do what the Fed has done. I contend the market will revolt because we are not compliant, we lack respect, we are anything but cohesive. Increase the temperature, change the mood, and we, as the masses, will revolt.